Benazir Bhutto, a Dynasty of Hope, Money and Daggers

The Rise and Fall of Pakistans First Lady

Benazir Bhutto: Power, Patronage, and Tragedy in Pakistan’s Dynastic Politics

This exposé accompanies my interview with French journalist Laurence Gourret, who spent over a decade embedded in the undercurrents of Pakistan’s political labyrinth. During her time there, she gained rare access to the country’s inner sanctums—conversing with prime ministers, diplomats, tribal kingmakers, and drug lords alike—until the ISI, Pakistan’s powerful intelligence agency, decided she had seen too much.

In our conversation, Laurence recounts how her early admiration for Benazir Bhutto—the glamorous, Oxford-educated symbol of modern Pakistan—gradually unraveled into a far more complex and unsettling portrait. What begins as a tale of hope and charisma transforms into a darker meditation on power, myth-making, and betrayal.

This is one of those true stories that feels stranger than fiction. I invite you to dive into this extraordinary journey—an intimate, disillusioned, and at times haunting exploration of the woman once hailed as Pakistan’s heroine. She was a woman who was twice elected prime minister, who saw here father hanged, one brother assassinated another one poisoned, a woman whose husband was first jailed for a decade and then became prime minister, and an woman who was ultimately undone by the very forces she tried to master.

Executive Summary

Benazir Bhutto’s political life was a study in contrasts – heralded abroad as a democratic reformer and feminist icon, yet often criticized at home as an autocrat in dynastic garb. This investigative report digs beneath the sanitized Western narratives to examine Bhutto’s rise and fall in the harsh light of Pakistan’s power politics. I begin with her dynastic origins, tracing how her father Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s authoritarian rule and nuclear ambitions set the stage for both Pakistan’s atomic arsenal and the Bhutto family’s political dynasty. I scrutinize Benazir’s own entanglements with the military establishment and intelligence agencies, expose how she alternately clashed with and compromised with Pakistan’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to secure and retain power. Her two terms as Prime Minister (1988–90 and 1993–96) were marred by mounting corruption allegations, suppression of rivals, and patronage-fueled governance that led to disillusionment among even her ardent supporters (theguardian.com, time.com). I revisit the chaotic end of her second government – from media exposés of graft to the shocking murder of her own brother, which fractured Pakistan’s elite and her family alike (merip.org).

Bhutto’s assassination in 2007, shrouded in mystery and marred by a botched investigation, is dissected with evidence from United Nations inquiries and insider accounts. I detail how serious security lapses and a subsequent cover-up – including the hosing down of the crime scene – raised suspicions of complicity or willful negligence by elements of Pakistan’s security establishment (theguardian.com). Direct quotes and declassified insights illuminate how the Taliban and Al-Qaeda were immediately blamed, even as Bhutto herself had presciently emailed that she would hold the Musharraf regime and intelligence services responsible if she were killed (npr.org).

Finally, I confront the myth versus reality of Bhutto’s legacy. Western media eulogies of Bhutto as an “exemplary democrat” and champion of the poor and women’s rights are contrasted with her “mixed at best” record on development and human rights (merip.org, latimes.com). I highlight voices of Pakistani women’s activists and journalists who observed that Bhutto did little to repeal draconian Islamist laws or uplift women during her tenure (latimes.com). Her Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), far from being a model of liberal reform, remained steeped in feudal patronage – led by one of Sindh’s largest landlord families (the Bhuttos and Zardaris) and failing to deliver on land reform or minority rights (merip.org).

In conclusion, I assess Benazir Bhutto’s enduring legacy in 2025. The Bhutto name still looms large in Pakistan’s civil-military tug-of-war: her son, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, carries the mantle of the PPP in a political arena dominated by an increasingly assertive military. Bhutto’s life and death underscore the perilous bargain of Pakistan’s transactional politics – a dance with the establishment that can uplift a leader to power but just as quickly cast them down. Her influence also persists in Pakistan’s nuclear posture. The bomb that her father zealously pursued – and which she safeguarded politically – now anchors a volatile standoff with India, rendering today’s Indo-Pakistani tensions all the more dangerous. As India and Pakistan face off with nuclear arsenals in 2025 amid periodic crises, Bhutto’s legacy is a cautionary tale: the promise of democratic change, undercut by dynastic ambition and power-brokered compromises, left unresolved the fissures that still threaten Pakistan’s stability and South Asian peace.

Benazir Bhutto in 1989 as Prime Minister, speaking to the press during a state visit to the United States. Internationally, Bhutto’s youthful charisma and Western education fed a narrative of a liberal reformer – a stark contrast to the criticism she faced at home over her governance.

From Nuclear Ambitions to Dynastic Power

The Bhutto saga begins with Benazir’s father, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a charismatic yet autocratic leader whose rule forged the template for Pakistan’s future power struggles. Zulfikar rode to power as a populist after Pakistan’s 1971 trauma, which was the searing national wound of losing half its country in a bloody civil war. But Zulfikar swiftly showed authoritarian tendencies. In early 1973, he dismissed the elected provincial government of Balochistan on dubious pretenses, an act that inflamed a bloody insurgency. Bhutto deployed the military in Balochistan for a four-year crackdown that left thousands of civilians dead (nation.com.pk). One Pakistani commentator scathingly described Prime Minister Bhutto at this time as a “true civilian dictator,” noting that his actions in Balochistan were a “barefaced mockery of democracy.”. Indeed, Bhutto refused to tolerate his party’s loss in Balochistan and the Northwest Frontier, using federal power to overturn election results and install loyalists despite having no mandate there. These strong-arm tactics – backed by imprisonment of opposition leaders and suppression of dissent – earned Bhutto infamy in those regions even as his supporters hailed him as a populist savior elsewhere.

Parallel to his domestic iron-fist, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto cemented a legacy that would reshape South Asia’s geopolitics: launching Pakistan’s pursuit of the atomic bomb. When India first tested a nuclear device in 1974, Bhutto’s resolve hardened. “We will eat grass, even go hungry, but we will have our own [atom bomb],” he vowed, declaring that Pakistan had no alternative but to develop nuclear weapons (tribune.com.pk). This oft-quoted promise – to sacrifice everything for nuclear parity with India – was emblematic of Bhutto’s grand strategy. He kick-started Pakistan’s clandestine nuclear program, laying its foundations by recruiting scientists and courting allies like China and North Korea for technical assistance. Pakistan’s first enrichment facilities and nuclear research institutions sprang up on his watch. The fervor of Bhutto’s nuclear ambition (and his refusal to abandon it) arguably contributed to his downfall; he believed Western powers, particularly the U.S. under Henry Kissinger, wanted him gone because of the bomb. Both Zulfikar and Benazir later suspected the CIA had abetted General Zia-ul-Haq’s coup in 1977, which overthrew Bhutto and led to his execution (en.wikipedia.org). True or not, Bhutto’s nuclear bequest endured: by 1998, Pakistan tested nuclear weapons, fulfilling his prophecy albeit at the cost of international sanctions and regional instability.

Yet Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s most immediate legacy was dynastic. After his hanging in 1979, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) became a family heirloom, passed to his widow Nusrat and 26-year-old daughter Benazir in exile. Bhutto had fashioned the PPP in his populist image, and now Benazir would burnish it with her own. In 1986, when a triumphant Benazir returned from exile to lead the anti-Zia democratic movement, frenzied crowds in Lahore chanted her name, seeing in her the wali (guardian) of Bhutto’s legacy. Thus began Benazir Bhutto’s rise – not merely as an individual politician, but as scion of a political dynasty that promised to restore Pakistan’s democracy and avenge Bhutto’s martyrdom.

Benazir’s ascent was intertwined with another family that would become equally notorious in Pakistan’s power circles: the Zardaris. Her 1987 marriage to Asif Ali Zardari, a businessman from a landowning Sindhi family, cemented an alliance that would define the PPP’s future (and taint its reputation). Zardari eventually earned the moniker “Mr Ten Per Cent,” reflecting a widespread belief that he took kickbacks on government contracts. During Benazir’s premierships, Zardari’s influence (despite holding no formal office initially) grew pervasive – and so did allegations of brazen corruption. By the 1990s, accounts of Zardari’s wheeling-dealing became legion: from sweetheart deals for Swiss companies to gold bullion import rackets and shady real estate ventures abroad. Perhaps the most infamous symbol of PPP corruption was the Surrey Palace affair. In the mid-1990s, a lavish 355-acre estate in Surrey, England – complete with a manor house dubbed Rockwood – was surreptitiously acquired through offshore companies linked to the Bhutto-Zardari family. When UK investigators uncovered the paper trail (shell firms in the Isle of Man and Liechtenstein fronting for the Bhuttos), it corroborated claims that kickbacks from Pakistani government deals had been laundered into foreign luxuries. The fallout was severe: these revelations helped precipitate the dismissal of Benazir’s government in 1996 and landed Zardari in prison on charges ranging from corruption to conspiracy in the murder of Benazir’s brother, Mir Murtaza Bhutto (theguardian.com).

Even as Zardari spent 11 years in custody through the 1990s and early 2000s without ever being conclusively convicted (reuters.com, theguardian.com), his reputation as a symbol of graft endured. In 2008, after Benazir’s assassination, he astonishingly catapulted from jailbird to Pakistan’s president under an amnesty deal. A Guardian report at the time noted the bitter irony: “With one bound, the man known as Mr Ten Per Cent has become Mr Clean – the man courted by the West as the leader who can tackle the Taliban.” Indeed, Western capitals conveniently overlooked Zardari’s sordid past when they needed a civilian partner in Islamabad. Meanwhile, Pakistani investigators quietly dropped cases, and Swiss prosecutors, citing lack of cooperation from Pakistan’s new government, unfroze some $60 million from Zardari’s secret accounts (theguardian.com). Those funds had been frozen since the 1990s amid evidence the Bhutto-Zardari duo took illicit commissions on Swiss contracts (reuters.com). The whiff of deal-making was unmistakable: Pervez Musharraf’s regime, under pressure to legitimize itself, promulgated a National Reconciliation Ordinance (NRO) in late 2007 that quashed corruption charges against Bhutto and Zardari, facilitating her fateful return from exile and effectively whitewashing Zardari’s record (theguardian.com).

In sum, by the time Benazir Bhutto first took office in 1988, she stood at the intersection of two powerful currents: the populist but authoritarian legacy of her father, and the rising tide of money politics exemplified by her husband. The dynastic principle – that the right to rule Pakistan almost belonged to the Bhuttos as a blood inheritance – buoyed her politically, but it also engendered a sense of entitlement that would prove double-edged. “The Bhutto family has a historic legacy of serving the nation,” PPP loyalists still proclaim (nation.com.pk). Yet, as the following sections reveal, that legacy was often as much about entrenching power and privilege as about public service.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1971, shortly before he became Pakistan’s ruler. He combined populist charisma with ruthlessness – dismissing an elected provincial government and unleashing military force in Balochistan when it defied him. His vow to obtain the atomic bomb “even if we have to eat grass” galvanized Pakistan’s nuclear program (tribune.com.pk), while his toppling in a 1977 coup paved the way for his daughter Benazir’s dynastic rise (nation.com.pk, nation.com.pk).

Complicity with the Military and the “Establishment”

From day one of her premiership, Benazir Bhutto’s relationship with Pakistan’s military and intelligence establishment was fraught with ambiguity – a mix of guarded cooperation, mutual suspicion, and occasional outright collusion. Pakistan’s power brokers, hardened by years of dominance under General Zia, viewed the young civilian Prime Minister with skepticism. Bhutto, for her part, understood that her survival depended on placating the Army and ISI even as she tried to assert civilian authority. The result was a series of uneasy compromises that saw Bhutto collaborating with the very forces that had brutalized her family.

In 1988, after winning Pakistan’s first free election in over a decade, the 35-year-old Bhutto struck a pragmatic bargain: she would not touch the military’s core interests – defense policy, the Afghan war, the nuclear program – if the generals let her govern on domestic matters. Indeed, army chief Gen. Mirza Aslam Beg and President Ghulam Ishaq Khan (an establishment figure) only allowed Bhutto to take office after extracting assurances she’d keep their Afghan proxy war on course (carnegieendowment.org). True to form, during her first term (1988–90), Bhutto left the ISI’s covert support of Afghan mujahideen largely intact, even as the Soviet withdrawal wound down. She kept on the ISI chief, Lt. Gen. Hamid Gul – an Islamist hardliner – presumably to avoid antagonizing the spy agency. But the distrust was mutual and deep: ISI operatives, with tacit military approval, reportedly conspired with opposition politicians in 1989 to topple Bhutto’s government in a scheme code-named Midnight Jackals. That plot failed narrowly, but it underscored that Bhutto was never fully in control – the intelligence services were watching.

Conversely, Bhutto did not hesitate to use the state machinery and intelligence agencies to her own advantage when she could. She was keenly aware that politics in Pakistan often operates on patronage and coercion behind the scenes. A telling example comes from Punjab in 1989: stymied by her rival Nawaz Sharif (then Chief Minister of Punjab) who commanded Pakistan’s largest province, Bhutto’s PPP launched a secret campaign to buy the loyalties of opposition legislators and orchestrate a provincial coup. According to Time magazine, “the party’s first acts after coming to power was a campaign to bribe and threaten legislators in Punjab” with the aim of overthrowing Nawaz’s provincial government. Her aides justified this skullduggery by claiming Nawaz had rigged the prior election – a claim “not supported by impartial observers.” When Nawaz struck back with equal ferocity – using police to harass PPP politicians – Bhutto unleashed federal agencies to cripple Nawaz’s business empire. Tax authorities audited Nawaz’s factories; state banks squeezed his family’s loans; and the PPP government even cut off financing to projects in Nawaz’s strongholds. Both sides engaged in a no-holds-barred patronage war, offering as much as $1 million to any parliamentarian willing to switch sides during a no-confidence vote against Bhutto in late 1989. In one almost comic twist, rival camps effectively kidnapped their own MPs for “safe-keeping” – sequestering them under guard to prevent defections as bags of cash floated around Islamabad’s political backrooms. Such was the transactional power dynamic of the era: Bhutto’s lofty rhetoric about democracy coexisted with a readiness to undermine democratic norms through bribes and intimidation, rationalized by the victor-take-all ethos born of Zia’s repression (time.com).

Beyond domestic politicking, Bhutto’s tenure also saw collaboration with foreign intelligence agencies in ways that undercut her reformist image. For instance, the Taliban’s rise in Afghanistan in the mid-1990s occurred on Bhutto’s watch and arguably with her government’s covert support. Her second term’s Interior Minister, Maj. Gen. (R) Naseerullah Babar, proudly celebrated as the “father of the Taliban”, was the architect of Pakistan’s pro-Taliban policy. Babar, a trusted Bhutto confidant, openly “made no bones about the fact that he was the father of the Taliban” and saw the militant group as a “strategic and political ally” that could secure Pakistan’s interests in Afghanistan. Under Bhutto and Babar, the Pakistani state provided arms, supplies, and training to the Taliban as they emerged in 1994–96 – viewing them as preferable to the anarchic mujahideen factions. Bhutto later tried to distance herself from the Taliban project once its extremism became evident, but by then the nurture was done. This episode illustrates how Benazir colluded with the military–jihadi complex when it suited short-term strategic aims, even if it meant empowering extremists who were anathema to her professed liberal values. Similarly, Bhutto maintained cordial ties with the CIA, which saw her as a useful ally, particularly during her exile and comeback. Declassified U.S. documents and memoirs suggest she shared intelligence on mutual enemies – for example, she reportedly passed on information about Sikh separatists to India’s government in the late 1980s as a goodwill gesture to Delhi and Washington. Such moves burnished her image abroad as a rational moderate, but within Pakistan they could appear as selling out national or Islamist causes (tribune.com.pk).

On the flip side, Bhutto’s attempts to assert civilian control over the ISI were met with stiff resistance. In 1989, she appointed a retired general of her choosing, Shamsur Rahman Kallu, as ISI chief – an unusual move intended to sideline hardliners. The military bristled, and Kallu’s influence was neutered by the army’s internal machinations. Later, during her second term, Bhutto again tried to tame the intelligence apparatus by creating a separate civilian counter-intelligence bureau, but to little avail. Both Bhutto and her rival Nawaz Sharif learned that Pakistan’s intelligence agencies were a law unto themselves – any leader who threatened their primacy would be undermined. Bhutto’s own ouster in 1990 was aided by the ISI’s covert funding of an opposition alliance (the IJI) to defeat her in elections; and in 1996, it is widely believed the military high command green-lit President Leghari’s dismissal of her government amidst myriad scandals (carnegieendowment.org).

An incident in Karachi during 1995 further exemplified Bhutto’s complex dealings with the security forces. Her government launched “Operation Cleanup” against the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), an urban opposition party in Karachi accused of militancy. Under Interior Minister Babar’s direction, police and paramilitary forces brutally suppressed the MQM, with streets turning into battlefields and allegations of extrajudicial killings mounting (tribune.com.pk). Bhutto gave Babar a free hand to crush what she saw as a threat to state authority – in effect sanctioning a mini-police state in Karachi. The operation was successful in denting the MQM’s armed wing, but it also earned Bhutto censure for human rights abuses and reinforced the pattern of using force to handle political problems. It did not escape notice that while she vehemently denounced state brutality under Zia, Bhutto was not above unleashing the security forces on segments of her own citizenry when facing dissent or disorder.

In summary, Benazir Bhutto’s time in power was characterized by a pragmatic if uneasy partnership with Pakistan’s permanent establishment. She tread a fine line – at times appeasing the generals and spymasters, at times attempting to marginalize them, and occasionally partaking in their dark arts of patronage and repression. This complicity was not lost on observers. As one analysis noted, Bhutto “adhered to liberal democratic ideals” in principle, but in practice her judgment was “carried away by the vengeful currents of Pakistani politics”time.com. She and the PPP fell back on the same tools of power – bribery, coercion, the backing of shadowy enforcers – that had propped up previous regimes. By using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house, Bhutto perhaps inevitably fell short of true democratic transformation. Instead, she became enmeshed in the establishment’s web, leaving many Pakistanis to wonder if the substance of her rule differed much from that of the military despots she decried.

Corruption, Collapse, and Disillusionment

Bhutto’s second term (1993–1996) began amidst high hopes but unraveled in spectacular fashion, engulfed by corruption scandals, governance failures, and bitter infighting among Pakistan’s elite. If her first government’s premature dismissal in 1990 could be blamed in part on a hostile establishment, the demise of her second was as much a self-inflicted collapse – a tale of broken promises and public disenchantment.

When Bhutto returned to power in 1993, Pakistan’s intelligentsia and masses alike expected her to have learned from past mistakes and Zia’s legacy. Initially, she talked of energizing the economy with privatization and spoke of advancing social reforms, including women’s rights. But as one Pakistani journalist observed, “few progressive measures were introduced” the second time around, and the lofty rhetoric soon rang hollow. Instead, allegations of corruption and nepotism that had dogged her first term only multiplied. Her husband, Asif Zardari – now officially a minister in charge of investment – gained notoriety as “Pakistan’s most powerful man” for his perceived ability to extract cuts from any major deal. International media ran almost daily stories in the mid-1990s detailing the Bhutto family’s ostentatious wealth and alleged kickback schemes (time.com). The New York Times, Washington Post, and others reported on multimillion-dollar mansions in England, luxury apartments in the U.S., and bank accounts in Switzerland tied to the Bhutto-Zardari orbit. Bhutto angrily dismissed many of these reports as opposition propaganda or “a political witch-hunt” orchestrated by her rivals (theguardian.com). Yet, the sheer volume of cases – from the Société Générale surveillance contract bribes to the Dassault Mirage jet kickback scandal – made the denials ring weak.

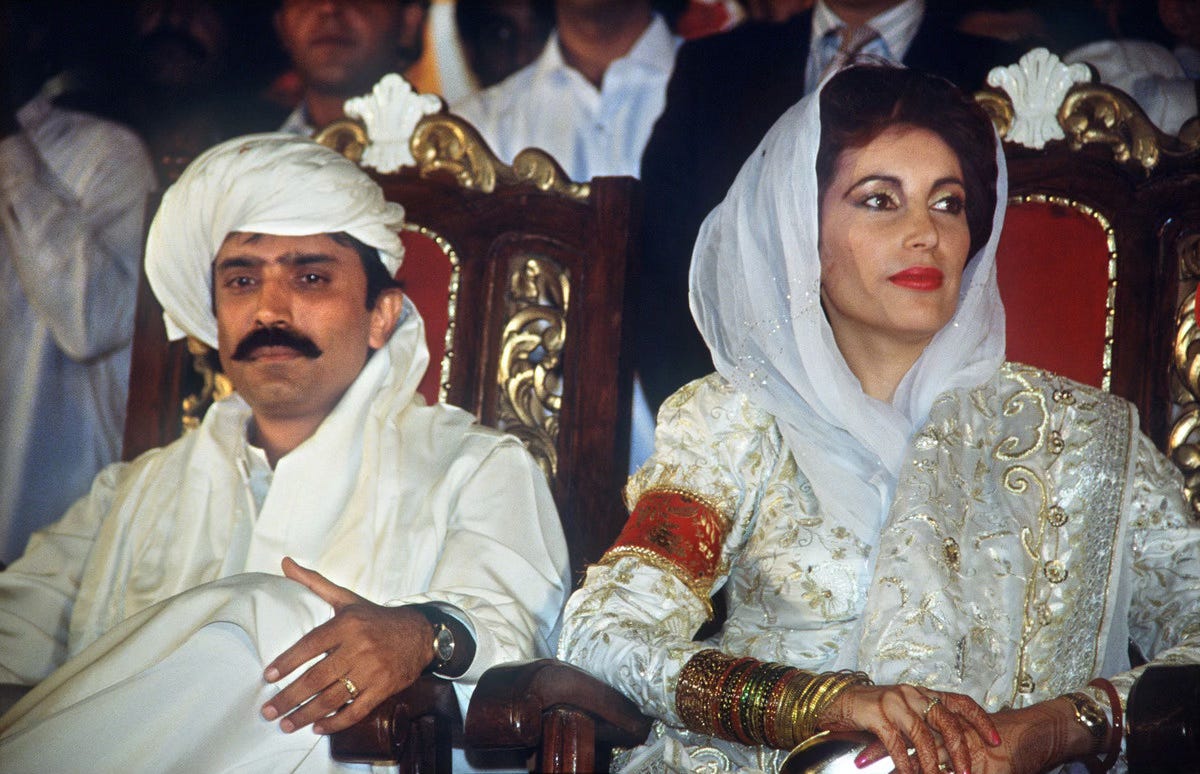

Benazir Bhutto at her wedding with Asif Ali Zardari in Karachi December 18, 1987.

The Pakistani press, which had grown bolder and freer in the 1990s, also turned on Bhutto’s government with a vengeance. Newspapers like The News and magazines like Friday Times (edited by Najam Sethi) ran exposés on the corruption and misrule. Cartoonists routinely skewered “Ten-Percent Zardari” as a pirate looting the national treasury. Even former allies became critics; for instance, Maleeha Lodhi, once close to Bhutto, lamented that the government “lost the moral high ground” due to its scandals (time.com).

Meanwhile, governance suffered. By 1996, Pakistan was mired in economic troubles: growth had slowed, debt was mounting, and basic services were faltering. Bhutto’s administration appeared ineffective and insular, more occupied with settling scores than policymaking. One glaring failure was her inability (or unwillingness) to repeal General Zia’s draconian Islamist laws, such as the Hudood Ordinances. She had campaigned as a progressive but in power she never confronted the religious right. Critics noted that not a single discriminatory law was struck down during her rule; even egregious practices like evidence laws that valued a woman’s testimony at half a man’s remained intact (latimes.com, latimes.com). Women’s rights activists, once among her staunch supporters, felt betrayed. “She’s a politician…not a women’s rights activist,” said one such activist bluntly in 1993, urging Bhutto to act rather than bask in her symbolic status as a female leader (latimes.com). Likewise, promised land reforms to break feudal holdings never materialized – unsurprising perhaps, given Bhutto’s own family were among Sindh’s largest feudal landlords (merip.org). To many, the PPP had become indistinguishable from the traditional elite parties when it came to perpetuating patronage and status quo.

The breaking point for Bhutto’s second government came with a series of shocks in 1996. In September that year, her younger brother Murtaza Bhutto – once a fiery rival who accused Benazir of betraying their father’s legacy – was gunned down along with his associates in a police encounter near his Karachi home. Murtaza’s death sent political temperatures soaring. Given the long-standing sibling rivalry and dynastic feud (Benazir and Murtaza had been locked in a bitter dispute over control of the PPP), suspicions swirled that elements within Benazir’s regime had a hand in the killing. Murtaza’s widow and daughter – Ghinwa and Fatima Bhutto – openly accused Benazir and Zardari of complicity (en.wikipedia.org). Fatima Bhutto, then a teenager, would later write that Benazir “covered up my father’s murder” by thwarting a full investigation, and she alleges Zardari was “personally involved” (merip.org). Whether or not the accusations were fair, the perception of fratricide within Pakistan’s foremost political dynasty horrified the nation. It also fractured the Bhutto clan: Benazir’s mother, Nusrat Bhutto, sided with Murtaza’s family and reportedly denounced Benazir, deepening the family schism (latimes.com).

And hanging over it all was the ghost of yet another brother—Shahnawaz Bhutto—who had died mysteriously in 1985, allegedly poisoned in his apartment in France. No one was ever held accountable. For a family that had come to symbolize Pakistan’s political destiny, the Bhuttos were now engulfed in something darker: a pattern of unexplained deaths, fraternal bloodshed, and silence.

Politically, the Murtaza affair eroded whatever credibility Bhutto had left. President Farooq Leghari, a stalwart of the PPP whom Benazir herself had elevated to the presidency, broke ranks. Citing “corruption, nepotism, and violation of law” – including the allegation that Bhutto’s government sanctioned police death squads – Leghari invoked his constitutional powers to dismiss Benazir’s government on November 5, 1996 (newsroom.ap.org). It was a stunning fall: Benazir went overnight from Pakistan’s most powerful person to a disgraced figure fighting a slew of court cases. Leghari’s removal order accused her administration of everything from looting state coffers to undermining the judiciary and “mismanaging the economy” into crisis (upi.com). Notably, one charge was that she had attempted to intimidate the Supreme Court – indeed she had a running clash with Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah, which further turned opinion against her. Bhutto’s dismissal also highlighted the “elite fracture” in Pakistan’s power structure: it wasn’t just the opposition or military that wanted her out, but even her handpicked president and segments of the liberal intelligentsia had lost faith.

In subsequent years, judicial verdicts and investigations confirmed many of the corruption charges. In April 1999, a Pakistani court convicted Benazir (in absentia, as she had left for London) and Asif Zardari of accepting kickbacks in the $100 million Cotecna/SGS Swiss inspection contract. They were sentenced to five years and fined $8 million each. Although the convictions were later overturned on appeal, the detailed evidence – money trails to Swiss accounts, offshore company records, testimonies of bribery – left an indelible stain. The Guardian noted this was “the first time a ranking politician [in Pakistan] has been convicted for corruption” and that even many of Bhutto’s traditional supporters felt let down by her rule. Voters certainly felt disillusioned: the PPP was trounced in the 1997 elections by Nawaz Sharif’s party, winning only 18 seats to Nawaz’s 134, a shellacking that bore testimony to public disgust. Bhutto’s once-adoring base in Sindh also shrank as the province was wracked by violence and the trauma of Murtaza’s killing (theguardian.com).

By the end of the 1990s, Benazir Bhutto’s image within Pakistan was at its nadir. She lived in self-imposed exile in Dubai and London, fighting legal battles and appealing to international opinion for a chance at redemption. It was a remarkable arc: from the hopeful young prime minister who rode into office pledging an end to poverty and dictatorship, to a twice-dismissed leader widely seen as having squandered her mandate. As one analysis aptly put it, “Many Pakistanis, including Bhutto’s traditional supporters, have felt let down by her…Public anger mounted as allegations of corruption emerged” (theguardian.com). The very fact that some Pakistanis came to sympathize with Bhutto’s claim that she was a victim of a “witch-hunt” by the Sharif government speaks to the cynicism – the people had seen this play out before, just with roles reversed (theguardian.com). To them, Bhutto’s downfall was not an anomaly but part of a pattern in Pakistani politics where each elected leader becomes mired in graft and misrule, only to be ousted and replaced by rivals who prove no less venal.

The collapse of Bhutto’s government also underscored that democracy in Pakistan remained hostage to an entrenched elite – be it feudal politicians like the Bhuttos, industrial barons like Nawaz, or the omnipresent military establishment. Benazir’s story was, in a sense, the story of Pakistan’s broader democratic collapse in the 1990s: a decade that began with exuberance for civilian rule after Zia, and ended with a return to military dictatorship (Musharraf’s coup in 1999) amid public disillusionment with the politicians who had bickered and plundered. Bhutto’s failures were a major part of that disillusionment. As the MERIP journal observed, her legacy was “far murkier – and far more disappointing – than a follower of the Western media may perceive”, given that her party “delivered on nearly none” of its promises on land reform, women’s rights, and social justice (merip.org). This gap between myth and reality would only grow more pronounced after her dramatic return and tragic assassination in 2007.

Assassination in Rawalpindi: The Murder and the Cover-Up

On December 27, 2007, Benazir Bhutto’s life was violently cut short in the garrison city of Rawalpindi – a place laden with grim symbolism in Pakistan (it was in the same city’s park that the country’s first PM, Liaquat Ali Khan, was assassinated in 1951). Bhutto was leaving an election rally, standing through the sun-roof of her armored SUV to wave at supporters, when shots rang out followed by a suicide bomb blast. In the ensuing carnage, at least 20 people were killed. Bhutto herself collapsed into the vehicle, fatally wounded. The shocking assassination of Pakistan’s best-known politician made headlines worldwide and plunged the nation into grief and rage. But almost immediately, it also became an object of controversy and conspiracy, as the truth of who was behind the murder and how it was allowed to happen seemed to slip further away with each passing day.

Within hours of Bhutto’s death, Pakistan’s Interior Ministry announced that Baitullah Mehsud, a Pakistani Taliban warlord with ties to Al-Qaeda, was the mastermind. They released an intercepted audio in which Mehsud allegedly congratulated fellow militants on Bhutto’s death. The government’s narrative held that a jihadi suicide bomber – perhaps motivated by Bhutto’s support for the U.S.-led War on Terror – had carried out the attack. Indeed, U.S. intelligence at the time also pointed to Al-Qaeda. Bruce Riedel, a former CIA official, opined that the assassination was “almost certainly the work of al-Qaeda or al-Qaeda’s Pakistani allies,” whose objective was to destabilize Pakistan and eliminate a secular political force (cfr.org). Bhutto had many enemies among Islamist extremists: she had outspokenly criticized the Taliban and even claimed Osama bin Laden had once plotted to bankroll a coup against her. Thus, the theory that jihadists struck her was plausible.

However, as details emerged, serious questions arose about the circumstances of the assassination and the conduct of Pakistani authorities before and after the murder. A United Nations Commission of Inquiry, tasked with investigating Bhutto’s killing, later delivered a damning report in 2010. It concluded that Bhutto’s death “could have been prevented” had proper security measures been taken – measures that were conspicuously absent that day (theguardian.com). Despite known threats to Bhutto by Islamist groups (there had been an earlier attempt on her life on October 18, 2007, when a bombing killed nearly 150 at her homecoming procession in Karachi), she traveled in an open-top vehicle and police failed to cordon off her route properly. The UN report condemned Pakistani officials for failing to protect Bhutto and noted that key local police deliberately blocked off the mobile phone jammers that were meant to prevent remote detonations – an inexplicable lapse (refworld.org, theguardian.com).

Even more suspicious was the post-attack investigation – or lack thereof. Within minutes of the blast, before forensic work could be done, local police infamously hosed down the crime scene with high-pressure water, destroying evidence (refworld.org). This astonishing act, caught on camera, led many to believe there was a concerted effort to cover up the truth. The UN Commission bluntly stated that the investigation was “severely hampered by intelligence agencies and other government officials, which impeded an unfettered search for the truth” (theguardian.com). In other words, Pakistan’s infamous “establishment” – code for the nexus of military and intelligence – was implicated in obstructing justice. The chief of Rawalpindi police and another senior official were later tried (and initially convicted) for negligence and evidence tampering, though they were eventually acquitted on appeal.

Benazir Bhutto herself had voiced fears of exactly such an outcome. In October 2007, after that first assassination attempt in Karachi, she wrote an email to her friend and U.S. spokesman Mark Siegel to be made public in the event of her death. In it, she blamed then-President Pervez Musharraf for denying her adequate security, and said if she were killed, Musharraf should be held “responsible”npr.org. She specifically mentioned that Pakistan’s intelligence serviceswere not providing the protection she needed (npr.org). This email, revealed by CNN and NPR after her death, was a bombshell: it suggested that Bhutto suspected elements within the regime might conspire in her assassination or at least facilitate it by standing down security. Mark Siegel later testified that Bhutto had begged the Musharraf government for better armored cars, jammers, and investigation into the Karachi bombing, but “none of which the government would provide” (npr.org). Musharraf, for his part, has vehemently denied involvement. Yet, in 2018, a Pakistani anti-terrorism court even indicted Musharraf in the Bhutto murder case, naming him an absconder for failing to appear (Musharraf was living in exile by then). The court’s charge sheet essentially alleged that Musharraf and others were part of a conspiracy to eliminate Bhutto or willfully did not prevent it, though he was never tried due to exile and later his death in 2023.

So, what explains the “mysteries” and multiple narratives surrounding Bhutto’s assassination? One theory holds that Islamist militants acted as triggermen, but rogue members of Pakistan’s security apparatus abetted the plot or at least wanted her gone. Bhutto had many enemies in the establishment: hardliners in the Army who distrusted her outreach to India and her popularity; ISI figures tied to jihadists who saw her as too pro-Western; even some politicians in the ruling party who feared her return in upcoming elections. For the military regime of the time, led by Musharraf, Bhutto’s impending electoral victory in 2008 elections threatened to upend their grip. Some analysts suggest elements of the military passively allowed the assassination by denying her security, calculating that her death would remove a thorn in their side. The UN report hinted at this, noting that officials at the highest levels “displayed a persistent lack of willingness to respond to Ms. Bhutto’s extremely serious security requests” and that this atmosphere essentially “constituted a green light for her assassination” (refworld.org).

There were also claims of prior warnings and foreknowledge that went unheeded. It emerged that CIA and British intelligence had intercepted communications in late 2007 indicating militants were planning to target Bhutto, and reportedly, the U.S. had warned Musharraf’s government. Additionally, after Bhutto’s death, Scotland Yard was invited to assist in determining the cause of death (whether from a bullet or the blast – even that was disputed because initial reports bizarrely claimed she died from hitting her head on the sunroof lever). The British forensics team concluded a bomber was the cause, aligning with the official account, but they did not investigate culpability. Meanwhile, Washington’s role came under scrutiny: U.S. diplomats had brokered the Musharraf-Bhutto deal (the NRO amnesty) enabling her return – some in Pakistan argue the Americans pushed her into a dangerous situation without ensuring her safety. Bhutto’s aides later said she felt the U.S. would “guarantee her security” in exchange for her cooperation with Musharraf, a guarantee that proved meaningless.

To this day, no mastermind has been convicted for Benazir Bhutto’s assassination. The young man identified as the suicide bomber died on the spot; five alleged Pakistani Taliban foot-soldiers arrested in the case were eventually acquitted due to lack of evidence. Musharraf, the only person formally accused of conspiracy, died a free man in exile. The case remains officially unsolved, shrouded by missing evidence and perhaps deliberate silence. A telling passage from the UN investigation said Bhutto’s assassination “was not the first time in Pakistan’s brief national history that a major political figure had been killed or died in mysterious circumstances – and it may not be the last” (files.ethz.ch), underscoring a pattern of impunity.

What is clear is that Bhutto’s murder removed a pivotal player at a critical moment. Whether one saw her as Pakistan’s best hope for democracy or as a deeply flawed leader, her presence would have profoundly influenced the country’s direction after 2008. Instead, her absence created a sympathy wave that helped her party win the 2008 election, but the PPP government under Zardari was weak, and the military soon reasserted dominance behind the scenes. The emotional outpouring after her death – riots erupted in Sindh, and mourners thronged to Garhi Khuda Bakhsh for her burial – reflected not only grief but also the deep frustration of a populace whose dream of stable civilian leadership kept being snatched away. In the end, Benazir Bhutto did not live to see whether she could redeem her legacy in a third term. Her death became, in a tragic way, her most consequential act, galvanizing attention on the dangers faced by those who challenge Pakistan’s status quo and the murky collusion between militants and elements of the state.

The Myth vs. Reality of Benazir Bhutto

In the Western imagination, Benazir Bhutto’s story reads almost like a fairy tale gone wrong – the elegant, Oxford-educated “daughter of the East” who broke the glass ceiling of a Muslim nation, only to be struck down by fanatics. She has been lionized as a martyr for democracy and even an icon of women’s empowerment. But within Pakistan and across the Global South, many view Bhutto with more nuance, if not outright skepticism. The mythical narrative of Bhutto as a spotless democratic heroine does not fully square with the complex reality of her political career, which was laden with compromises and contradictions.

It is undeniable that Bhutto’s symbolic significance was immense. As the first woman to lead a Muslim-majority country, she inspired women across the Islamic world. She endured years of imprisonment and exile under Zia, refusing to give up on politics when many colleagues quit or cut deals. Her personal courage – returning to Pakistan despite threats to her life – cannot be questioned. These qualities earned her reverence abroad. Western media, especially in her later years, tended to cast Bhutto in an exemplary light. Upon her death in 2007, outlets like the BBC, CNN, and Time magazine painted her as “an exemplary democrat” who championed moderation against extremism (merip.org). They highlighted her articulate advocacy for democracy in forums like the United Nations and how she projected a tolerant image of Pakistan in her book Reconciliation. Hillary Clinton eulogized Bhutto as someone who “stood for the future of Pakistan” in terms of women’s rights and modernity.

Yet, Pakistani analysts and human rights observers often offer a starkly different appraisal. Sameer Dossani, writing in MERIP, noted that Western obituaries were marked by “overstated piety” and tended to overlook the murkier aspects of her tenure (merip.org). In reality, Bhutto’s actual governance was “little different than her predecessors and successors” in failing to better the lot of the average Pakistani (merip.org). Under her watch, poverty and feudal inequities remained entrenched, and the political economy – dominated by a military-business elite – changed little.

One key area where the myth diverges from reality is Bhutto’s record on human rights and women’s rights. Internationally, she was hailed as a feminist trailblazer. But domestically, many activists were disillusioned. Renowned women’s rights groups like the Women’s Action Forum (WAF) and individuals such as Asma Jahangir were critical of Bhutto’s inaction on Islamic laws that oppressed women. During 1988-90, Bhutto made no move to repeal the Hudood Ordinances or the Law of Evidence that disadvantaged women (latimes.com). Sexual violence and honor killings remained rampant issues that her government did not systematically tackle. “Some of her most vocal critics are Pakistani women’s groups, who say she did almost nothing to help women during her previous term,” the Los Angeles Times reported bluntly in 1993 (latimes.com). Bhutto did appoint a couple of women to prominent posts (e.g., she named a female advisor on women’s affairs and a female ambassador to Washington latimes.com), but these gestures were token compared to the structural reforms activists sought. In her campaigns, Bhutto often spoke about women’s empowerment, yet as one observer put it, “Bhutto barely breathed a word about women’s issues during the [1993] campaign, and since coming to power, there have been few concrete improvements” (latimes.com). The scathing verdict of a Pakistan-based women’s advocate captured it: “She’s a politician…not a women’s rights activist” (latimes.com). In other words, Bhutto prioritized political expediency over women’s emancipation when the two clashed.

Similarly, Bhutto’s image as a champion of democracy and civil liberties is complicated by her own tactics in power. For instance, press freedom groups recall that her government was not above pressuring journalists and media that got too critical (though outright censorship was far worse under others). Her use of the Security Forces to quell dissent – be it the military operation in Karachi or the heavy-handed response to protests – mirrored the authoritarian playbook at odds with her democratic persona. Human Rights Watch’s reports from the mid-90s document that torture and custodial abuse by police continued unabated during her government, and political prisoners (including some of her MQM opponents) were allegedly mistreated. Furthermore, Bhutto’s PPP, despite its populist rhetoric, remained feudal in character. As MERIP noted, the PPP relied on votes of the rural poor but was seen to represent the interests of big landlords – “the Bhuttos themselves, along with the family of Asif Ali Zardari, are among the largest landlords in Sindh” (merip.org). This feudal entitlement sometimes manifested in arrogance and aloofness from the plight of the masses. It’s telling that after Bhutto’s death, her last will and testament bequeathed the party leadership to her husband and son, cementing the dynastic principle and “feudal tradition” in the PPP (merip.org). There was no internal election or consultation – the mantle simply passed as if by divine right, something hard to reconcile with the democratic ideals she professed.

Even on fighting extremism, where Bhutto is often lionized, the ground reality was nuanced. Yes, she rhetorically opposed Islamic extremism and had planned to crack down on the Taliban and their Pakistani sympathizers had she won in 2008. But critics point out that during her rule, sectarian militant groups (like the anti-Shia Sipah-e-Sahaba and others) were not curtailed effectively – in fact, sectarian violence soared in the 1990s. And as discussed, her government’s nurturing of the Taliban contradicted her enlightened moderate image. This duality – of saying one thing to international audiences and sometimes doing another at home – fed cynicism among Pakistanis, who are used to leaders playing to Western galleries while maintaining patronage politics domestically.

Thus, the legacy of Benazir Bhutto is deeply ambivalent. Many Pakistanis today respect her courage and sacrifice – she died trying to reclaim democracy from a military ruler – but they also remember the baggage of corruption and misrule that accompanied her administrations. In Pakistan’s polarized narrative landscape, Bhutto is neither fully vilified nor fully absolved. The PPP’s supporters still venerate her as Shaheed Mohtarma (Martyred Madam), invoking her martyrdom to claim moral high ground. In contrast, her detractors invoke the corruption cases and her perceived elitism to argue that she, like other mainstream politicians, failed Pakistan’s poor.

Internationally, however, the “Benazir myth” of a secular saint remains strong, partly due to a lack of awareness of Pakistan’s internal dynamics. This myth was reinforced by her eloquent advocacy on the world stage – for example, in her final years she spoke strongly against the threats of Al-Qaeda and the Taliban’s oppression of women, which resonated in Western capitals post-9/11. It also helps that she cut a glamorous, cosmopolitan figure, making her a media darling abroad. Yet the disconnect between these narratives can lead to oversimplification. As one Pakistani commentator wrote, “the legacy of Benazir Bhutto is far murkier — and far more disappointing — than a follower of the Western media may perceive” (merip.org).

In recent years, some scholars and books have tried to bridge this gap. Her niece Fatima Bhutto’s memoir Songs of Blood and Sword portrays Benazir as power-hungry and complicit in fratricide, which is undoubtedly one side of a personal vendetta but adds to the non-hagiographic perspective. Other biographers highlight her personal evolution – from a somewhat imperious ruler in the ’90s to a more mature, perhaps chastened leader in 2007 who talked about reconciliation and combating extremism genuinely. The truth likely lies in a complex middle: Benazir Bhutto was both a product of Pakistan’s elitist, patronage-driven political culture and one of the few voices who could articulate democratic aspirations on the world stage.

Finally, there is the question: What did Benazir Bhutto truly leave behind for Pakistan? Her supporters would say she left an inspiration – that a woman could lead and that democracy is worth fighting for. They also credit her with more tangible contributions: for instance, during her terms some economy liberalization occurred, and she did initiate women’s police stations and courts (latimes.com). Her detractors retort that she left unfulfilled promises and a sullied democratic experiment, which opened the door to yet another military takeover. Both views have merit. Perhaps her most enduring legacy is the PPP itself – a party that, despite all its flaws, has remained a key player in Pakistani politics, espousing federalism and rights for minorities (Bhutto was a vocal proponent of minority religious rights and appointed a Christian, Julius Ribeiro, to her cabinet which was unprecedented). The PPP survived her death and even returned to government in 2008-2013 under Zardari. But tellingly, that government too did not dramatically reform the system; it mostly muddled through, content with completing a term without being ousted – an achievement by Pakistan’s standards, but hardly transformative.

In the end, Benazir Bhutto’s life symbolizes both the potential and the perils of Pakistan’s quest for democracy. The potential in that she embodied the hopes of millions for a progressive, pluralistic Pakistan; the perils in that she could not escape the vortex of corruption and power politics that have repeatedly blighted those hopes. As Pakistan moves forward, Bhutto’s myth can indeed inspire, but the reality of her shortcomings offers equally important lessons about the need for deeper structural change – beyond the charisma of any one leader – to fulfill the promise of “Bread, Clothing, Shelter” (Roti, Kapra, Makan as the PPP slogan goes) that she once made to the downtrodden.

Relevance in 2025: Bhutto’s Legacy and Pakistan’s Fault Lines

Nearly two decades after Benazir Bhutto’s assassination, Pakistan continues to grapple with many of the same fault lines she contended with – a testament to both the resilience of those problems and the mixed nature of her legacy. As of May 2025, Pakistan’s political landscape is once again tumultuous. The country has oscillated between civilian governments and direct or indirect military rule in the years since Bhutto’s death, underscoring the unresolved civil-military imbalance that she tried, but ultimately failed, to correct. Her Pakistan Peoples Party, now led by her son Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, remains a player but no longer commands the nationwide appeal it once did. However, understanding Bhutto’s legacy is crucial to deciphering Pakistan’s present crises – including escalating tensions with India, internal political strife, and the ever-looming specter of the military in politics.

Civil-Military Dynamics: Bhutto’s confrontations and accommodations with the military set precedents that are evident even today. After her passing, the PPP under Asif Zardari actually oversaw a rare period (2008–2013) where a civilian government completed a full term, albeit with the Army still controlling key portfolios (defense, security policy) behind the scenes. In those years, the PPP consciously avoided antagonizing the generals – a strategy born from Bhutto’s hard lessons in the 90s. For example, the PPP government quietly extended the Army chief’s tenure and toed the line on foreign policy, remembering how resistance had cost Bhutto dearly. This pragmatism allowed a semblance of stability but at the cost of empowering the military’s role as Pakistan’s ultimate arbiter. Fast forward to 2022–2023: the PPP found itself in a coalition to oust populist rival Imran Khan which we briefly discussed in the interview, a move that many saw as the old establishment parties (PPP and PML-N) aligning with the military to sideline a common threat (thehillstimes.in, scmp.com). Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, foreign minister in that coalition, walked a tightrope – echoing his mother’s calls for democracy while supporting a government that critics say was propped up by the Army’s behind-the-scenes maneuvers. In this sense, the PPP today carries forward Bhutto’s dual legacy of rhetorically championing civilian supremacy but often tactically yielding to the Army’s supremacy in practice. As one commentary noted recently, the major parties including PPP “have certain resilience” having survived martial law, but also a tendency to “close ranks with the establishment when expedient” – a nod to how Bhutto’s party has navigated the post-Imran crackdown alongside the military rather than opposing it (aljazeera.com).

Dynastic Politics and the PPP’s Posture: Benazir’s legacy also lives on through dynastic politics which remain alive and well. Bilawal, only 19 at his mother’s death, was anointed PPP chairman per her will – an explicit passing of the torch. Now in his mid-30s, Bilawal has come into his own, even earning the role of Pakistan’s foreign minister (2022–2023). He invokes his mother and grandfather’s name frequently, framing the PPP as the party of “martyrs for democracy.” However, the PPP’s current posture is a far cry from the radical reformism of Zulfikar’s time or even the populist vigor of Benazir’s early campaigns. Today, it governs Sindh province and projects itself as a moderate force – neither anti-establishment like Imran Khan’s PTI tried to be, nor as conservative as Nawaz Sharif’s base. In essence, the PPP has become an established part of the status quo, arguably more concerned with preserving its regional power (in Sindh) and negotiating deals with power brokers than with mass mobilization or social revolution. Some analysts even suggest the military finds utility in the PPP’s presence as a known, controllable entity – much as they once found Bhutto useful to checkmate other rivals.

On the Indo-Pakistani front, Bhutto’s impact is palpable in the form of nuclear deterrence and enduring rivalry. The nuclear weapons that her father initiated and she staunchly preserved (she was proud that her government in 1990 did not roll back the program under U.S. pressure) are now central to South Asia’s security calculus. As of 2025, India and Pakistan remain nuclear-armed adversaries with no substantive dialogue. The Kashmir conflict still simmers (India’s revocation of Kashmir’s autonomy in 2019 inflamed tensions anew) and border skirmishes erupt periodically. In February 2019, for instance, the two countries came to the brink of war after a suicide bombing in Kashmir and subsequent Indian airstrikes in Pakistan; nuclear threats were thinly veiled during that crisis. One could argue that Zulfikar and Benazir’s nuclear bequest is a double-edged sword: it has perhaps deterred full-scale wars (there has been no all-out war since 1971) but it has also internationalized the stakes of every skirmish, making each crisis perilous for the region and world. Bhutto herself recognized this delicate balance; in her last years she advocated confidence-building measures with India, yet firmly opposed any rollback of Pakistan’s nukes, reflecting a consensus view in Pakistan that the bomb is national insurance – a view originally propagated by her father’s “eat grass” resolve (tribune.com.pk).

As Indo-Pak tensions escalate or de-escalate, Bhutto’s legacy is invoked in different ways. Indian hawks often paint her as having been two-faced – citing how the Taliban rose under her – to argue that Pakistan’s leaders cannot be trusted, thus feeding the cycle of hostility. Pakistani doves, on the other hand, recall Bhutto’s attempts at peace (for example, she held a fruitful summit with India’s Rajiv Gandhi in 1989 and signed accords to ease tensions) as a model for engagement that current leaders could emulate. In 2025, the region stands at a crossroads: with hardline governments on both sides and a volatile border, the need for visionary statesmanship is dire. Bhutto’s life offers lessons on both what to do and what not to do. Her initial openness to dialogue with India, and recognition that Pakistan must root out extremism internally, are positive guideposts. Conversely, her pandering to militant proxies and inability to resolve core disputes (like Kashmir) show the dangers of short-termism.

Escalating Indo-Pakistani tensions in May 2025 can also be contextualized by Bhutto’s legacy. She often warned that Pakistan’s democracy was necessary to achieve peace with India – a democratic Pakistan, she argued, would be more accountable and less likely to sponsor cross-border militancy or brinkmanship. As Pakistan currently grapples with a democratic backslide (with Imran Khan imprisoned and his party suppressed and the military’s role again overt), one might surmise that the country’s posture towards India could become more rigid or adventurous, since the check of public debate is weakened. It’s notable that during fully military regimes (like under General Musharraf) Pakistan both engaged in intense conflict like Kargil in 1999 and also surprising peace overtures (the 2003-2007 peace process). Under hybrid regimes (like Bhutto’s and Sharif’s tenures), policy oscillated but there was at least some civilian input. Today’s dynamics will test whether any of Bhutto’s ideals – such as curbing Islamist extremism which fuels Indo-Pak tensions – have been internalized by Pakistan’s power structure. The recent appointment of Bilawal to lead an international mission countering India’s narrative on terrorismconnectedtoindia.com suggests Pakistan still values the Bhutto name on the world stage. Indian officials likely recall Benazir’s own words from the 1990s when she spoke against militancy; ironically, now her son must defend Pakistan’s record to a skeptical global community, even as India accuses Pakistan of harboring terrorists. This underscores how unresolved the issues from Bhutto’s time remain.

Finally, Benazir’s enduring legacy on Pakistan’s society and political culture in 2025 is subtly profound. She personified the idea that Pakistan could be modern, pluralistic, and led by merit rather than martial might. While her actual governance didn’t fulfill that vision, the aspiration persists among Pakistan’s educated classes and youth, many of whom still cite Bhutto as an inspiration for entering public service or activism (including a significant number of women leaders in politics and media today who came of age during her premierships). The PPP, though diminished, still rallies people using Bhutto’s slogans of “democracy is the best revenge.” In the face of rising authoritarian tendencies and censorship in 2025, the memory of Bhutto’s charismatic defiance of dictators serves as a rallying cry for some – reminding that Pakistan has a history of popular resistance that she helped embody.

Conversely, her flaws have also served as cautionary tales. The term “Mr Ten Percent” for corruption is part of the lexicon, often trotted out whenever a new scandal emerges, implicitly linking back to Zardari and by extension Bhutto’s era. Civil society activists argue that unless Pakistan breaks the cycle of corrupt dynastic politics (exemplified by Bhutto and Sharif families), true democracy will remain elusive. Thus, calls for accountability and transparency often invoke the 1990s as what not to repeat. Even Imran Khan’s rise was built on an anti-corruption plank that implicitly damned the Bhutto-Zardari legacy.

In sum, as of 2025, Benazir Bhutto’s shadow looms in both hopeful and cautionary ways. Regionally, the nuclearized standoff with India that her father initiated and she sustained is the precarious backdrop to any future war or peace – a legacy that ties her to South Asia’s fate. Domestically, the struggle between civilian rule and military dominance, and between progressive values and regressive forces, continues along the contours that defined Bhutto’s life. Pakistan today is at another inflection point, not unlike the one in 2007. The lessons from Benazir Bhutto’s journey – her bravery in challenging dictatorship, her failings in governance, her ultimate martyrdom – remain vitally relevant as Pakistan navigates the turbulent waters of its politics and as its people yearn for a stable, democratic future that has long been promised but never fully delivered.

Timeline of Major Events

June 21, 1953 – Benazir Bhutto is born in Karachi, Pakistan, into the influential Bhutto family. Her father is Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a rising politician.

December 1971 – Following Pakistan’s defeat in the Bangladesh Liberation War, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto becomes President (later Prime Minister) of Pakistan. Benazir witnesses her father’s ascent to power.

1973 – Prime Minister Zulfikar Bhutto dismisses Balochistan’s elected provincial government, triggering an insurgency and military crackdown in Balochistan nation.com.pk. He also launches Pakistan’s secret nuclear weapons program, famously declaring Pakistanis would “eat grass” if necessary to get the bomb tribune.com.pk.

July 5, 1977 – General Zia-ul-Haq topples Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in a military coup. Benazir and her family are put under house arrest.

April 4, 1979 – Zulfikar Ali Bhutto is executed by the military regime after a controversial trial. Benazir, age 25, becomes the de facto leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) alongside her mother Nusrat.

1981–1984 – Benazir endures imprisonment and solitary confinement under Zia’s martial law. In 1984, she goes into exile in London. She co-founds the Movement for Restoration of Democracy.

April 10, 1986 – Benazir Bhutto returns to Pakistan from exile. Huge crowds welcome her in Lahore, signaling popular support against Zia’s dictatorship.

August 17, 1988 – General Zia is killed in a plane crash. Elections are called, paving the way for a democratic transition.

December 1, 1988 – Benazir Bhutto becomes Prime Minister, the first woman to lead a Muslim-majority country. Aged 35, she heads a fragile coalition. Internationally hailed as a democratic milestone merip.org.

1989 – Bhutto survives a no-confidence vote engineered by the ISI. Her government is accused of bribing MPs; opposition also bribes MPs – an era of horse-trading politics time.com. She meets Indian PM Rajiv Gandhi and signs agreements to improve ties.

August 6, 1990 – President Ghulam Ishaq Khan dismisses Bhutto’s first government on charges of corruption and mismanagement. New elections are called, which Bhutto’s PPP loses.

1990–1993 – Bhutto leads the opposition. Corruption allegations mount (e.g., the discovery of Swiss bank accounts). She gives birth to her third child in 1992.

October 19, 1993 – After elections, Bhutto is elected Prime Minister for a second term. This time, her PPP has a clearer majority. She pledges economic reform and women’s empowerment.

1994–1995 – Under Bhutto’s watch, the Taliban emerge in Afghanistan with support from her interior minister, Naseerullah Babar tribune.com.pk. In Karachi, Bhutto orders a military operation against the MQM, which turns bloody.

September 20, 1996 – Benazir’s brother Mir Murtaza Bhutto is killed in a police encounter in Karachi. The incident deepens a rift in the Bhutto family and tarnishes Benazir’s government amid allegations of a cover-up merip.org.

November 5, 1996 – President Farooq Leghari dismisses Bhutto’s second government, citing corruption, abuse of power, and Murtaza’s murder. Bhutto is again out of power; her husband Asif Zardari is arrested and jailed theguardian.com.

1997–1999 – Nawaz Sharif’s government pursues corruption cases against Bhutto. In 1999, a court convicts Benazir and Zardari of corruption (they appeal) theguardian.com. Bhutto goes into self-imposed exile to avoid imprisonment.

October 12, 1999 – General Pervez Musharraf stages a coup, toppling Nawaz Sharif. Bhutto remains in exile (London/Dubai), vocal against the military regime from abroad.

2002 – Under Musharraf, a law is passed barring prime ministers from serving a third term – seemingly to prevent Bhutto’s return. PPP comes in second in elections, but Musharraf excludes Bhutto and Sharif from power.

October 5, 2007 – Musharraf issues the National Reconciliation Ordinance (NRO), an amnesty dropping corruption charges against Bhutto and others, as part of a deal to share power. This clears the way for her return.

October 18, 2007 – Bhutto returns to Pakistan after 8 years. Her homecoming procession in Karachi is hit by a suicide bombing, killing ~150 supporters. Bhutto survives, narrowly, and blames extremist threats and lack of security npr.org.

December 27, 2007 – Benazir Bhutto is assassinated in Rawalpindi, shot at and then hit by a suicide bomb while leaving a rally. She is 54. Al-Qaeda/Taliban are blamed by the government, but controversy over a possible official cover-up ensues as the crime scene is washed and critical evidence lost theguardian.com.

2008 – In the wave of sympathy, the PPP wins the February elections. Bhutto’s widower, Asif Ali Zardari, becomes President of Pakistan, and a PPP-led government rules until 2013, completing a full term.

2010 – A UN Inquiry issues a report on Bhutto’s assassination, concluding it was preventable and that Pakistani authorities failed to protect her and impeded the investigation theguardian.com

2013 – PPP loses power in elections amid corruption fatigue. Bhutto’s son Bilawal takes on a more active political role as the Bhutto-Zardari heir.

2018 – A Pakistani court acquits several accused in Bhutto’s murder and declares Musharraf an absconder. The masterminds remain officially unidentified.

2022 – Bilawal Bhutto Zardari becomes Pakistan’s Foreign Minister in a coalition government. He invokes his mother’s legacy in international forums, advocating for democracy and warning against extremism, much as she did.

2025 – Benazir Bhutto’s legacy continues to shape Pakistan’s politics. The PPP, though regionally confined, still commemorates her martyrdom annually, and her portrait often adorns rallies championing democracy. Indo-Pak tensions remain high in a nuclearized environment – a sobering reminder of Zulfikar and Benazir’s nuclear legacy and the unresolved issues she once grappled with, now passed on to a new generation of leaders.

Very comprehensive article. Also a wonderful interview with Laurence Gourret! Good to hear her decisive view on Imran Khan's honesty and integrity. The US fingerprints are all over his case, the world should not forget about him.