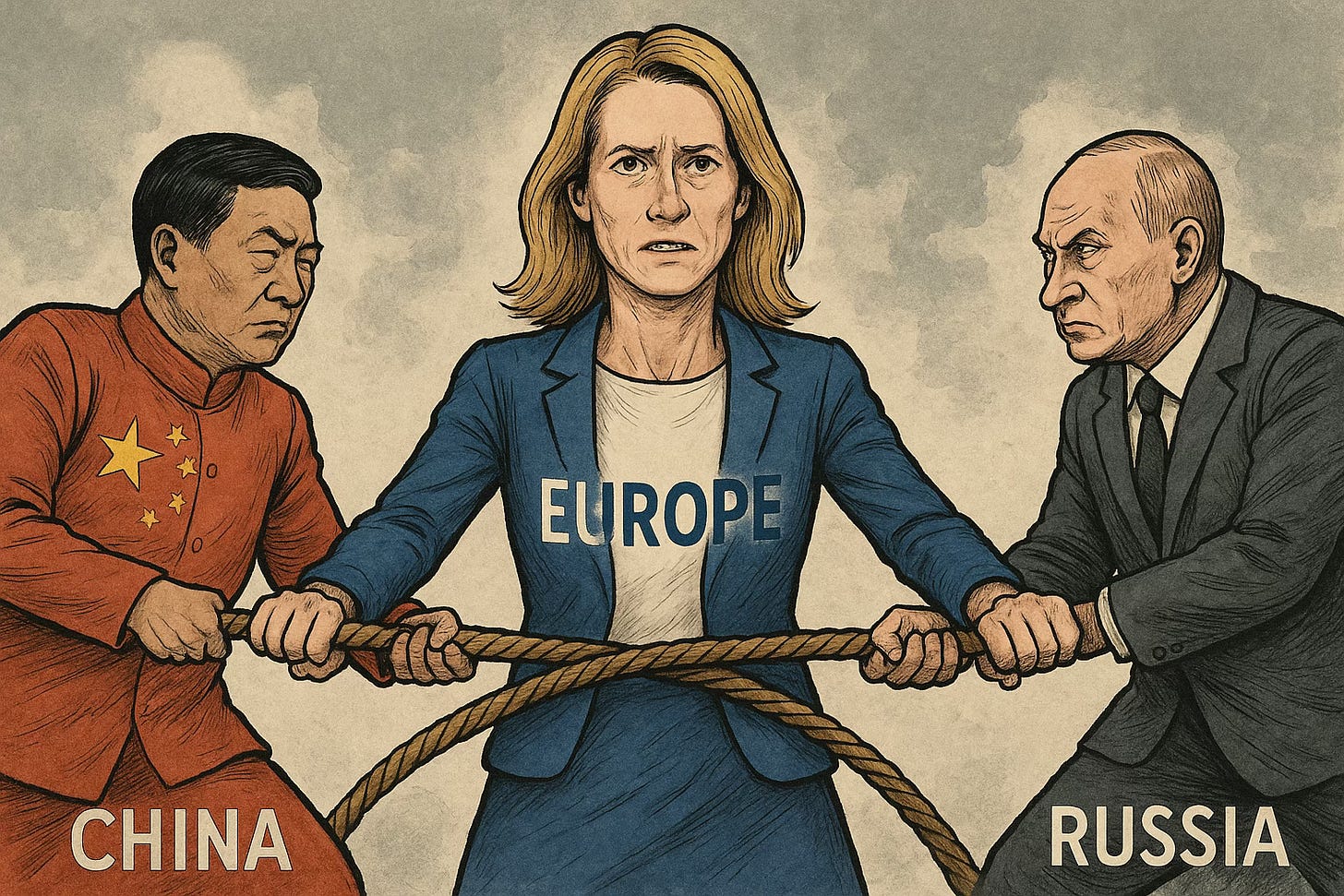

How Unelected Bureaucrats Are Steering Europe Toward a Two-Front Confrontation with Russia and China

Are Kaja Kallas and Ursula von der Leyen pushing it too far?

I’ve spent months tracing the fault-lines between Tallinn and Brussels, and what I’ve uncovered is not for the faint-hearted or the skimmer. In this report I will show how a once-obscure Estonian lawyer now shapes decisions that could pull Europe into simultaneous showdowns with both Moscow and Beijing. If you advise, legislate, invest, or command—read on. What follows could save your budget, your strategy, and, in the worst case, your citizens’ lives. Ignore it, and tomorrow’s headlines may write themselves.

Executive Summary

Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas speaking at a 75th anniversary commemoration of Soviet deportations in March 2024. Her family’s experience under Stalin’s terror fuels her conviction that “the aggressor will never change and will never stop,” as she warned while linking Russia’s current war in Ukraine to past crimes news.err.ee.

Kaja Kallas’s Rise and Agenda:

Estonia’s Kaja Kallas, a former tech lawyer turned politician, has rapidly ascended from leading a 1.3-million nation to becoming the European Union’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs (as of December 2024). Shaped by a family history scarred by Soviet repression – her mother was deported to Siberia as an infant – Kallas views modern Russia as a direct heir to that “ultimate evil”news.err.ee. As Estonia’s prime minister (2021–2024), she earned a reputation as one of Europe’s fiercest Russia hawks politico.eu, unflinchingly advocating military aid to Ukraine and urging a hard line against both Moscow and, increasingly, Beijing. Upon taking up the EU foreign policy chief role, Kallas vowed to apply the same resolve Europe-wide, framing Ukraine’s fight as a civilizational struggle that will determine Europe’s security principles for decades theguardian.com. Critics, however, worry that Kallas – alongside European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen – is pursuing an escalatory agenda without a clear democratic mandate, one that could entangle Europe in a de facto two-front conflict with nuclear-armed great powers.

Unelected Elites and the “Power Without Mandate” Problem:

Neither Kallas nor von der Leyen were directly elected by European voters to their EU posts, yet together they have leveraged institutional levers to accelerate Europe’s militarization. Von der Leyen has pushed an “era of rearmament” narrative and unveiled massive defense plans (the “ReArm Europe” package to mobilize up to €800 billion dw.com), while Kallas has co-authored an EU Defence Readiness White Paper calling for a five-year military buildup to face down Russia atlanticcouncil.org. These initiatives include the new European Defence Investment Programme (EDIP) (a joint procurement fund initially budgeted at €1.5 billion ceps.eu), fast-track arms production schemes (like ASAP for ammunition), and an off-budget Ukraine Assistance Fund of €5 billion per year under the European Peace Facility europediplomatic.com. Yet such moves have often bypassed typical democratic scrutiny. In 2025, the European Commission – led by von der Leyen and High Rep. Kallas – even attempted to use an emergency treaty clause (Article 122 TFEU) to push through a €900 billion arms initiative (“SAFE”) without full European Parliament approval responsiblestatecraft.org. This legal maneuver, which was unanimously struck down by Parliament’s legal affairs committee as overreach responsiblestatecraft.org, epitomizes the governance gap: major security decisions being made by “hawks” in Brussels, Paris, and Warsaw “rather than broad support from Europe’s diverse populations”responsiblestatecraft.org. Public skepticism is indeed significant – polls show citizens in key countries like France, Italy, and Spain do not favor higher military spending euronews.com, and 62% of Italians oppose cutting social budgets to rearm euronews.com. Observers warn that elites’ fear-driven narrative of perpetual threats is pressuring all EU states to align with a Russia-centric security agenda, even when some (Hungary, Slovakia, etc.) advocate a negotiated end to the Ukraine war responsiblestatecraft.org or prioritize other concerns like migration responsiblestatecraft.org. This democratic deficit risks eroding trust in EU institutions just as they embark on their most ambitious military posture in modern history.

Toward a Two-Front Confrontation – Russia and China:

Kallas argues that standing up firmly to Russia now will deter China later. “If you don’t want problems with China, you have to be really strong on Russia,” she urged, suggesting that a decisive defense of Ukraine would make Beijing “think twice” about aggression (e.g. against Taiwan) politico.eu. In Brussels forums, she has explicitly linked Europe’s Russia policy to its China strategy, contending that Western resolve in Ukraine sends a message to China’s Xi about the costs of military adventurism politico.eu. As High Representative, Kallas has pushed for tighter EU alignment with Washington’s hard line on Beijing – viewing Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea as a connected block sestry.eu. European security officials report that in early 2025 Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi privately told Kallas that China “does not want to see Russia lose in Ukraine” because a Russian defeat would free the US to focus entirely on China russiamatters.org. This geopolitical calculus raises the stakes: a prolonged Western campaign to hobble Moscow could drive Beijing and Moscow into a closer strategic counter-alliance. Nevertheless, under Kallas’s influence the EU has inched toward a more confrontational stance on China – from scrutinizing Chinese tech and investments to vocal support for Taiwan’s status quo – even as some member states worry about economic blowback. The emerging doctrine from Tallinn to Brussels is uncompromising: democracies must not appease dictators, whether in the Kremlin or Zhongnanhai, lest aggression be rewarded and multiplied.

Risks, Blind Spots, and Blowback: Detractors of Kallas’s hawkish course caution that her rhetoric “makes it seem we are at war with Russia, which is not the EU line,” as one EU official complained politico.eu. By treating the Ukraine conflict as a zero-sum showdown between Europe and Russia – a frame Kallas justifies by invoking Estonia’s own precarious history – EU leaders like her and von der Leyen may be foreclosing diplomatic off-ramps in favor of maximalist war aims. The governance gap exacerbates this: Kallas’s initial months as High Rep. saw multiple missteps where she “floated heavy proposals” for more arms without consulting member states politico.eu. Southern European countries (Spain, Italy) and others less Russophobic bristled at being railroaded into escalatory measures, with diplomats privately accusing Kallas of “still acting like a prime minister” rather than a consensus-building EU envoy politico.eu. Hungary’s government has been openly critical – Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó blasted “alarmingly dangerous” talk from some European leaders about sending troops to Ukraine and warned that such steps “would set the continent ablaze”europediplomatic.com. Meanwhile, Europe’s economies have already weathered energy price spikes, inflation, and loss of Russian markets; a broader war or severe rupture with China could inflict far greater pain (one estimate pegs a NATO-Russia war shock at –1.3% of global GDP in year one theweek.com, and a Taiwan conflict at –10% of global GDP bloomberg.com). European public opinion, too, is a fault line: war fatigue and anxiety are growing as the Ukrainian counteroffensive stalls and casualty figures climb into the hundreds of thousands theguardian.com. The question “how does this end?” looms large. Yet Kallas and like-minded “Euro-atlantists” thus far remain focused on victory rather than compromise – insisting that “Putin cannot win this war… or his appetite will grow.” as Kallas wrote in 2022 yahoo.com. The coming 12–18 months will test whether Europe’s more cautious voices can rein in this agenda, or whether Kallas, von der Leyen and allies will succeed in committing the EU to an expansive, long-term confrontational stance on both its eastern and far-eastern fronts.

Report Roadmap:

The full report below provides an in-depth investigative look at: (1) Kaja Kallas’s biography and the formative experiences driving her hardline views; (2) the mechanisms through which she and other unelected EU elites are steering policy (often outpacing democratic checks); (3) concrete policy decisions and defense-industrial mobilization that pave pathways to wider war; (4) internal EU dissent, strategic blind spots, and economic interdependencies that challenge the hawks’ narrative; and (5) scenario analysis of potential escalation trajectories – from a contained proxy war to a regional NATO-Russia clash to a worst-case global conflict – including a five-year cost assessment of each. The report concludes with policy options, urging consideration of restraint, revitalized arms control (e.g. via the OSCE), and diplomatic engagement to prevent Europe from sleepwalking into a two-front war, which is in line with the arguments the former UK Diplomat Ian Proud presented in my recent interview with him.

Biographical Deep-Dive: Kaja Kallas – Genealogy, Education, and Political Rise

Family Legacy of Resistance: Kaja Kallas’s worldview is profoundly shaped by her family’s experiences under Soviet occupation. She often recounts the harrowing story of March 1949, when her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother were deported from Estonia to Siberia by Stalin’s regime news.err.ee. Her mother Kristi was just 6 months old at the time, bundled in a cattle wagon for a 29-day journey, surviving only thanks to strangers who warmed the infant’s diapers against their bodies news.err.ee. Kallas’s grandfather was sent to a Siberian prison camp; miraculously, her family members all returned alive years later news.err.ee. But the ordeal left an indelible lesson. “This evil lives on in Russia,” Kallas warned in a 2024 speech commemorating the deportations, drawing a straight line from Soviet crimes to Putin’s aggression in Ukraine news.err.ee. For Estonians of her generation, history never fully “ended” in 1991 – memories of mass repression fuel a deep mistrust of Moscow’s intentions. Kaja’s great-grandfather, Eduard Alver, was himself a prominent figure in Estonia’s fight for independence a century ago (he commanded the Estonian Defence League during the 1918–1920 War of Independence) politico.eu. Thus, patriotism and defiance run in her blood. In 1988, as the Soviet system began to crack, 11-year-old Kaja stood with her father at the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. “Breathe the air of freedom,” Siim Kallas told his daughter then politico.eu – crystallizing the family’s credo that freedom must be fought for and never taken for granted.

A Politicized Childhood and the 1991 Turning Point: Kaja’s father, Siim Kallas, was a leading architect of Estonia’s rebirth. A dissident economist during the perestroika era, he helped steer Estonia to independence and later served as foreign minister (1995), prime minister (2002–03), and one of Estonia’s first European Commissioners (2004–2014) spiegel.de. Growing up in such a household, Kaja was immersed in politics from a young age. She recalls August 20, 1991, when Soviet tanks rolled after Estonia declared independence: “I was 14, and very afraid I would not see my father again. I knew all the stories of what Russians do to those who speak up,” she said spiegel.de. The family’s relief when Estonia ultimately broke free only reinforced Kaja’s conviction that peace and freedom are fragile. In her view, Western Europe’s 1945 was Eastern Europe’s 1991 – war and oppression didn’t end for Estonians until the Soviet collapse spiegel.de. This helps explain why she bristles at calls for quick peace with Putin now: “Peace does not always mean peace,” she repeats like a mantra, noting that for Estonia after World War II, peace simply meant decades of Stalinist tyranny spiegel.de. Such lived history informs her blunt message to Western leaders urging Ukraine to negotiate: “violence continues even after the bombs stop, if an aggressor remains in place” spiegel.de.

Education and Early Career – From Tech Law to Politics:

Despite her eminent lineage, Kaja Kallas was determined to prove herself on her own merits. After earning a law degree in the late 1990s, she specialized in European competition and tech law – fields then dominated by men, where colleagues recall her as energetic, sharp, and unfazed by the glass ceiling politico.eu. She worked in private practice and even led the Estonian Patent Office’s legal department, developing an expertise in innovation and digital economy. By her early 30s Kaja was a partner at a major law firm, yet felt unfulfilled. “I want to have a bigger impact,” she told her brother at the peak of her legal career politico.eu. For a time she even mused about quitting to be a golf caddy in Australia politico.eu. Instead, public service beckoned. In 2011, at age 33, Kallas ran for Parliament under the liberal Estonian Reform Party (which her father co-founded). She won a seat the next year spiegel.de, quickly dispelling media chatter that she was just “Siim’s daughter” or, as some chauvinists sneered, a pretty face without substance sestry.eu. Kaja steadily built her own profile, championing digital innovation and entrepreneurship in the legislature. In 2014, she took her talents to Brussels as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP). There, she earned respect across party lines – Politico named her one of the top influential MEPs – by mastering complex dossiers on the digital single market and energy. She was present at historic moments, such as the 2014 signing of the EU–Ukraine Association Agreement, which she saw as “continuing my father’s work of expanding Europe” spiegel.de. (Siim Kallas had negotiated Estonia’s EU entry; now Kaja was helping bring in countries like Ukraine.) Her pro-business, pro-Europe stance was summed up by a mentor: “She’s economically conservative, very pro-free-market, but also very socially liberal, young and dynamic… staunchly pro-European and anti-Putin” washingtonpost.com.

Reform Party Leader and Prime Minister:

In 2018, at age 41, Kaja Kallas was elected leader of the Reform Party, Estonia’s main center-right political forcewashingtonpost.com. She took over a party that champions NATO, EU integration, and low taxes – and which had dominated Estonian politics since the 1990s (sometimes derided as the party of the establishment elite to which Kaja undeniably belonged). After a short stint in opposition, Kallas became Estonia’s first female Prime Minister in January 2021. She assumed office with a reformist agenda but quickly found herself governing in crisis mode: first the COVID-19 pandemic and then, in 2022, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It was in this crucible that Kallas truly forged her international reputation. While some Western European leaders hesitated to send arms to Ukraine in early 2022, Kallas “sprang into action”, as Der Spiegel noted – in January 2022, weeks before the war, she was already urging emergency aid to Kyiv and preparing Estonia’s own weapons shipments spiegel.de. At the Munich Security Conference in February 2022, she publicly warned anyone willing to listen about the Kremlin’s playbook: “First, demand the maximum. Second, present ultimatums. Third, don’t give an inch – there will always be people in the West who offer you something” politico.eu. Such candor, coming from the leader of a tiny Baltic state, initially got eye-rolls (the “same-old message from the Baltics” routine spiegel.de). But after Russia attacked, Kallas’s long-standing admonitions – fortify NATO’s flank, stop Nord Stream 2, Putin only understands strength – suddenly looked prescient. The world media beat a path to Tallinn, and Estonia’s 45-year-old PM became, in the words of Spiegel, “one of Europe’s highest-profile leaders” seemingly overnight spiegel.de. Domestically, she won re-election in March 2023 in a landslide, with voters endorsing her staunch support for Ukraine despite economic pain (Estonia suffered nearly 20% inflation in 2022, partly due to cutting off Russian energy) washingtonpost.com. Her campaign posters featured a leaping squirrel – Reform’s symbol – embodying agility and hard work spiegel.de. Kallas’s slogan to Estonians was essentially endure the hardship, it’s worth it for freedom. The electorate agreed, handing her party 37 seats (in a 101-seat parliament) washingtonpost.com. “People see Putin’s Russia right across the border,” an analyst noted. “They are apparently willing to pay that price” for security washingtonpost.com.

From National to EU Stage – A ‘Firebrand’ Diplomat:

By mid-2024, Kaja Kallas was being mentioned for top international roles. She was on shortlists for NATO Secretary-General sestry.eu and had become a regular in forums with leaders like Biden, Macron, and Scholz. When EU officials sought a replacement for Josep Borrell as High Representative (the bloc’s foreign policy chief) after the European elections, Kallas’s name quickly rose to the top. Even French President Macron – whom she had once publicly humiliated by torpedoing his outreach to Putin – conceded that Kallas’s convictions had proven right. (Back in June 2021, Kallas boldly blocked a Merkel–Macron proposal to invite Putin to an EU summit, pointedly asking, “A summit on what? What is it for?” – embarrassing Merkel and drawing Macron’s scorn politico.eupolitico.eu. Yet three years later, those leaders nominated her for the High Rep job politico.eu.) On December 1, 2024, Kallas formally became the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, the first woman and first Estonian to hold the post politico.eu. Politico Europe headlined: **“Europe’s next top diplomat is ready to be undiplomatic”*, noting her reputation for plain-speaking and her narrow focus on Russia politico.eupolitico.eu. An unnamed European diplomat quipped, “If you ask Kallas where Africa is, she might say ‘south of Russia’,” reflecting concerns that she would be a single-issue diplomat fixated on the Kremlin at the expense of broader global engagement politico.eupolitico.eu. However, many insiders were optimistic. “Kallas will be a breath of fresh air,” said one Western European foreign minister, praising her energy and the impact she had as PM of a small country punching above its weight politico.eu. In Brussels, Kallas is seen as an embodiment of the Baltic/Nordic school of foreign policy: values-driven, Atlanticist, and intolerant of Realpolitik pandering to autocrats. With her friend Ursula von der Leyen heading the Commission (dubbed “Queen Ursula” by both admirers and critics for her dominant style), and Kallas as High Rep, two women now effectively steer the EU’s external relations – neither directly elected by Europe’s people, both deeply convinced of the righteousness of a hard line against Europe’s adversaries.

Power Without Mandate: EU’s Democratic Deficit in Foreign Policy Leadership

Unelected, Unapologetic: Ursula von der Leyen and Kaja Kallas share more than just a hawkish outlook – they are both products of Europe’s elite consensus and rose to power through appointment rather than popular vote. Von der Leyen, a former German defense minister, became European Commission President in 2019 despite not running as a lead candidate in the European Parliament elections (a controversial backroom deal saw her anointed by heads of government). Kallas, as High Representative, was selected by EU leaders in 2024 and approved by the new European Parliament, but of course, no citizens ever cast a direct ballot for “EU foreign minister Kallas.” This is by design – the High Rep is part of the Brussels technocracy. However, the aggressive use of EU instruments under their leadership has exposed the governance gap: decisions with vast strategic impact are being made with limited democratic oversight. In theory, EU foreign policy is intergovernmental (each of the 27 member states has a veto on major positions). In practice, the Commission and High Rep have cleverly expanded their sway. For example, under von der Leyen the Commission repurposed an off-budget mechanism, the European Peace Facility (EPF), to fund lethal arms deliveries to Ukraine – a first in EU history theguardian.com. Over €5 billion in weapons (from rifles to missiles) have been financed via the EPF since 2022 theguardian.com, even though the EU treaties never envisioned Brussels bankrolling war. The Orwellian irony of a “Peace Facility” buying arms was not lost on observers theguardian.com. Yet von der Leyen and Borrell (the outgoing High Rep) defended it as necessary improvisation in an existential crisis. Kallas, as Estonia’s PM, strongly supported this shift and pushed to institutionalize it: “The EU is living up to its commitments. The Ukraine Assistance Fund turns our words into action,” Borrell declared in late 2023 when member states agreed to top up the EPF with a dedicated Ukraine Assistance Fund (UAF) of €5 billion per year europediplomatic.com. The UAF’s creation – essentially a multi-year EU arms kitty – underscores how far the EU moved from its old soft-power comfort zone. It was done outside normal EU budget rules (to avoid member-state or parliamentary vetoes on the spending). Indeed, legal and procedural bypasses have become a hallmark of this new era.

Bypassing Parliament and Consensus:

Perhaps the starkest example was the Commission’s push in early 2025 for a package called SAFE (Security Action for Europe). Rather than go through the lengthy co-decision process with the European Parliament, von der Leyen’s Commission invoked Article 122 of the Treaty – an emergency clause usually meant for crises like natural disasters – to try to fast-track SAFE with only a weighted vote of governments, sidestepping the Parliament responsiblestatecraft.org. The rationale was that urgent defense measures couldn’t be hamstrung by potential vetoes or slow democratic deliberation responsiblestatecraft.org. High Rep. Kallas was fully on board with this maneuver; she lent “alarmist rhetoric” to justify it, portraying the security threats as so dire that extraordinary means were needed responsiblestatecraft.org. However, this raised red flags across the political spectrum. In April 2025, the European Parliament’s legal affairs committee unanimously struck down the Commission’s legal basis, asserting that normal democratic procedure must be followed for such a transformative shift responsiblestatecraft.org. MEP Eldar Mamedov wrote that using Article 122 in this way “weaponized” a crisis tool to avoid scrutiny and eliminate vetoes – calling it a “dangerous delusion” driven by Brussels hawks like von der Leyen and Kallas responsiblestatecraft.org. The episode highlighted an internal institutional check: even a generally pro-Ukraine, pro-defense European Parliament balked at being relegated to the sidelines. (Notably, the Parliament actually supports increased defense spending in principle – a broad majority of MEPs passed resolutions endorsing rearmament responsiblestatecraft.org – but they insisted on doing it the right way, through proper legislation rather than executive fiat.)

The Commission’s attempted overreach fed into a narrative of a “war Cabinet” in Brussels accruing powers without mandate. As Responsible Statecraft bluntly summarized, “Commission hawks, led by Ursula von der Leyen…and High Representative Kaja Kallas, have leaned on fear-driven narratives, exaggerating external threats…to justify this rush”responsiblestatecraft.org. They pressured all member states to align with a hardline agenda, “often at odds with their own priorities”responsiblestatecraft.org. Hungary and Slovakia’s calls for a negotiated settlement in Ukraine, or Italy and Spain’s greater worry about Mediterranean migration, found little reflection in Kallas’s security discourse responsiblestatecraft.org. Instead, any dissenting view risked being swept aside by qualified-majority votes or legal acrobatics. This dynamic – a determined policy core vs. reluctant periphery – has shades of earlier EU crises (e.g. the eurozone debt crisis) where technocratic decisions outran popular consent. Here, though, the stakes are war and peace.

Kallas’s Leadership Style – Catalyst or Bulldozer?

Since becoming High Rep, Kallas has earned both plaudits and pushback for her proactive (critics say unilateral) approach. Within days of starting the job, she tweeted that “the EU wants Ukraine to win this war” politico.eu – language more explicit than many member states use, as some prefer phrasing about “letting Ukraine defend itself” or “achieving a just peace.” Diplomats from countries like France and Germany were reportedly uneasy that Kallas was freelancing on messaging so soon politico.eu. “She is still acting like a prime minister,” griped one diplomat, implying Kallas hadn’t shifted from leading a sovereign country (where she could speak her mind) to being a consensus-builder for 27 countries politico.eu. Over her first few months, multiple incidents fueled this perception: Kallas circulated a 2-page memo to EU foreign ministers right after the February 2025 Munich Security Conference, urging them to urgently find 1.5 million artillery shells and billions in aid to offset a potential U.S. shortfall politico.eu. Importantly, she did this without pre-consulting major countries like France – the proposal “came out of nowhere” on a Sunday night, catching many off guard politico.eu. Moreover, she suggested each country contribute a quota of shells proportional to GDP politico.eu – a move clearly aimed at nudging big economies (Germany, France) who, per capita, had given less to Ukraine than the Baltics or Poland. While Eastern and Nordic diplomats privately applauded Kallas’s audacity (finally forcing the laggards to “dig deep”) politico.eu, others saw it as heavy-handed and even “coercion” politico.eu. Under pushback, Kallas had to scale down her “million shells” ambition to €5 billion for artillery rounds as an initial step politico.eu. An EEAS (EU External Action Service) official later defended her, saying: “They [EU leaders] hired a head of state for a reason – not to quietly moderate, but to push things forward. Many people argue we’re in 1938 or 1939. It’s not time to hide behind process. If European leaders keep saying ‘more aid to Ukraine’, okay, time for deeds not just words.” politico.eu. This view suggests that Kallas’s mandate, in the eyes of hawks, is precisely to be a wartime consigliere who cuts through the dithering. We are at a historical inflection, goes the argument, so don’t mind a bit of procedural bruising. Indeed, Kallas was chosen because she’s a wartime leader: “They hired a head of state for a reason… to push, not to find the lowest common denominator,” said the EEAS insider politico.eu.

The dilemma, however, is that the EU is not a unitary state – it’s a union of democracies where any perception of Brussels imposing decisions can fuel backlash. The near-failure of von der Leyen’s confirmation vote in 2019 (she squeaked by with a tiny majority amid complaints about her backroom selection) and the constant North–South, East–West tug-of-war in EU politics are reminders that legitimacy is the Union’s soft underbelly. With European Parliament elections in 2024 delivering gains for nationalist and Euroskeptic forces, Kallas and von der Leyen have to tread somewhat carefully or risk triggering institutional crises. Already, Kallas’s brash comment in early 2025 that “the free world needs a new leader” – tweeted after a contentious Trump–Zelensky meeting – rattled some allies politico.eu. While many Europeans were outraged by Trump’s hostile attitude toward Ukraine, most governments still wanted to avoid publicly insulting a sitting U.S. president. A senior diplomat noted, “Most countries don’t want to inflame things with the United States. Saying that isn’t what leaders wanted to put out there” politico.eu. In sum, Kallas’s transition from national to EU level has been marked by an assertive push to maintain momentum on the hard line, but it has also exposed fissures: differing threat perceptions, unease over democratic accountability, and the perennial question of how far Europe’s institutions can go in steering security policy without broader public buy-in.

Von der Leyen’s Centralization and Controversies:

Ursula von der Leyen, as Commission President, has been another key figure in this governance puzzle. Though not the focus of this report, it’s worth noting that von der Leyen has concentrated significant power in the Commission’s hands, especially in external affairs. She famously declared hers a “geopolitical Commission” in 2019, presaging the activist role she’d take during the Ukraine war – from personally brokering gas deals to supplying generators to Kyiv during winter blackouts. However, she too operates as one remove from direct voter accountability. Critics have dubbed her leadership style as imperial: a Politico exposé described her powerful chief of staff as the “quiet killer” behind “Queen Ursula’s throne,” controlling the flow of decisions politico.eu. Her habit of announcing major initiatives (like the €750 billion post-COVID recovery fund or punitive sanctions on Russia) with minimal consultation has irked even some heads of government. For example, von der Leyen negotiated a secret text exchange with Pfizer’s CEO for vaccine purchases, prompting an EU ombudsman rebuke over transparency. Such episodes add to a narrative that Europe’s executive elites are making deals over citizens’ heads.

In the defense realm, von der Leyen’s Commission has proposed breaking long-standing taboos, such as suspending EU fiscal deficit rules to allow a defense spending surge dw.com. In March 2025, she rolled out the “ReArm Europe” plan which envisages allowing member states to exceed the 3% GDP deficit limit by up to 1.5% of GDP for defense – potentially unleashing €650 billion in extra military outlays over 4 years dw.com. Additionally, she pledged €150 billion in EU loans to governments for defense investments dw.com. These dramatic steps were triggered by a scenario few imagined: a hostile U.S. administration (Donald Trump returned to power in 2025) cutting off all military aid to Ukraine dw.com. When that happened, von der Leyen convened an emergency summit, urging Europe to step up as its own guarantor. “We are in the most momentous and dangerous of times… Europe is ready to massively boost its defense spending,” she proclaimed dw.com. Significantly, Germany’s Green foreign minister Annalena Baerbock – usually an advocate of diplomatic multilateralism – endorsed the rearmament plan as “an important first step” toward “peace through strength” dw.com. This shows that even some traditionally skeptical voices have been swept into the consensus that more military power equals more security.

Yet outside the halls of power, publics are not entirely convinced. The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) poll in mid-2024 found majorities in 11 of 15 surveyed EU countries opposed to increasing defense spending at the expense of social programs euronews.com. In Italy and Spain, for instance, the war in Ukraine has always been a distant issue compared to jobs or migration; their citizens are lukewarm about pouring billions into arms. “European governments are unlikely to receive public support for direct military involvement [in Ukraine],” wrote the ECFR’s Ivan Krastev and Mark Leonard, cautioning that while elites talk of a existential fight, voters remain wary of open-ended commitment seuronews.com. Nationalist parties like Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France (poised to challenge Macron’s centrists) tap into this wariness. They argue EU leaders are risking European prosperity and even security by antagonizing Russia and potentially China without a clear mandate.

In summary, Europe’s current foreign policy leadership – exemplified by Kallas and von der Leyen – is pushing the envelope of what the EU has historically done. They have marshaled legal creativity (sometimes to the point of controversy) to fund war efforts, and personal diplomatic clout to shape narratives. But this concentration of decision-making in unelected hands, justified by the urgency of war, comes at a cost. It sidelines some voices and may store up a backlash, whether in the form of parliamentary revolt, electoral victories for anti-establishment forces, or simply eroding trust in the EU project among ordinary Europeans. The long-term sustainability of an assertive EU foreign policy likely depends on bridging this gap – finding ways to involve citizens and national parliaments in debates over war and peace. Otherwise, the “democratic deficit” becomes a strategic liability, potentially undermining the unity that Kallas and von der Leyen say is essential to confront Moscow and Beijing.

Pathways to War: Escalatory Policies, Defense-Industrial Ramp-Up, and Rhetorical Brinkmanship

Militarization on Fast-Forward: Under Kallas’s and von der Leyen’s guidance, the EU has embarked on an unprecedented military ramp-up, effectively transforming itself from a pacific economic union into an actor preparing for potential great-power conflict. The policy decisions since 2022 map out several pathways by which escalation could occur – intentionally or inadvertently. One pathway is through the sheer scale and scope of arms transfers to Ukraine. By providing ever more sophisticated weapons, European countries risk crossing Russian red lines. Already, what began with helmets and medical kits in early 2022 progressed to anti-tank missiles, then HIMARS rocket launchers, then tanks, and now discussions of fighter jets and long-range missiles. Kallas has been at the forefront of urging new thresholds: she was among the first to call for Europe to send Western battle tanks to Ukraine and pressed reluctant allies to “not hesitate” over advanced systems. Each time a taboo is broken (e.g. Germany agreeing to send Leopard 2 tanks after immense pressure), Russia responds with ominous warnings. While to date Moscow has largely limited its responses to energy blackmail, nuclear rhetoric, and incremental mobilization, there’s a latent risk that if the West were to help Ukraine strike deep into Crimea or Russia proper, the Kremlin could escalate in unforeseen ways (cyberattacks on European infrastructure, direct strikes on NATO supply convoys, etc.). Kallas tends to dismiss such concerns as overblown fear-mongering – she argues Putin always threatens escalation to sow division, and the only effective counter is to call his bluff. “If you are firm and not giving them what they want, it’s more probable you won’t have more wars,” she said, implying weakness invites further aggression politico.eu. Her stance encapsulates deterrence-through-strength: push back hard now to avoid a wider conflict later.

However, critics counter that this mindset leaves no face-saving exit for Russia and might actually precipitate the direct NATO–Russia clash everyone fears. French President Emmanuel Macron, for instance, while supporting Ukraine, has repeatedly emphasized the need to avoid “humiliating” Russia and has floated that eventual security guarantees might be needed for Russia as part of a peace deal – remarks that drew ire from Kallas and others. Yet Macron’s concern is that a cornered nuclear-armed regime could lash out if it perceives the war as existential. Kallas’s rebuttal is that any concession to Moscow now would only pause the conflict, not end the threat. This rhetorical framing – that “Russia must be defeated” (Kallas has said Ukraine “has to win the war” decisively spiegel.de) – inherently raises the stakes and potentially the costs of the war. It commits Europe to a maximalist outcome that Russia is unlikely to accept without extreme measures or internal change. In that sense, the hawks’ rhetoric could become a self-fulfilling prophecy: by insisting that only total victory is acceptable, they may indeed make the war one of survival for Putin, thus increasing the likelihood he takes desperate actions.

Defense-Industrial “Revolution”: Another pathway to escalation is the rapid militarization of Europe itself, which can trigger an arms race dynamic vis-à-vis Russia (and even China) and entrench a more confrontational posture. The EU has launched or expanded at least three major defense initiatives in response to the war:

European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS) and Investment Programme (EDIP): In March 2024, the Commission rolled out EDIS, a roadmap for Europe’s defense industry expansion ceps.eu. A core element is the EDIP – a regulation to spur joint procurement among member states and boost manufacturing of critical capabilities (drones, missiles, etc.) within the EU. The EDIP is modest at inception (only €1.5 billion allocated ceps.eu), essentially merging two short-term tools (EDIRPA for procurement and ASAP for ammo production) ceps.eu. But it’s seen as a prototype for much larger permanent programs. EU Commissioner Thierry Breton has stated bluntly that EDIP would need €100 billion to truly scale Europe’s defense base – indicating the level of ambition among some in Brussels ceps.eu. That figure dwarfs anything previously spent by the EU on defense. If realized, it would mean the EU (collectively) becoming one of the world’s top military spenders. The prospect of a heavily armed EU is cheered by Atlanticists (finally Europe pulling its weight in NATO) but not jeered by Moscow, which has long accused the EU of being NATO’s accomplice. Kremlin propagandists already paint EDIP and related schemes as confirmation of their narrative that “the West” is preparing for war on Russia. Thus, while EDIP itself is defensive (joint procurement to deter Russia), its implementation could feed threat perceptions that make de-escalation harder.

“ReArm Europe” and Member State Rearmament: Von der Leyen’s ReArm Europe plan, unveiled in March 2025, essentially greenlights EU countries to break past peacetime budget constraints and reorient their economies toward arms production on a wartime footing dw.com. By proposing to exempt defense spending from deficit rules, Brussels signaled that guns over butter is acceptable policy. The plan could unlock an extra €650 billion of national military spending in just four years dw.com. This is a seismic shift for countries like Germany, which for decades spent only ~1.2% of GDP on defense. (Already after 2022, Germany created a €100 billion special fund to upgrade its Bundeswehr, and other countries announced double-digit percentage boosts.) If sustained, this European rearmament will, by sheer economic weight, far outstrip Russia’s capabilities over time. Strategically, that is meant to deter Russia from future aggression. But in the interim – as Russia feels militarily weaker relative to a rising NATO/EU – it might actually act more aggressively or opportunistically while it still can (a classic security dilemma). NATO intelligence estimates Russia’s army needs 3–5 years to rebuild from its Ukraine losses atlanticcouncil.org. The EU’s White Paper that Kallas co-authored warns that by 2028 or so, Moscow could again threaten neighbors if unimpeded atlanticcouncil.org. This timeline puts pressure on Europe to plug its defense gaps quickly – and perhaps pressure on Russia to achieve gains before NATO’s full might comes to bear. In effect, Europe and Russia are in a race: Europe to arm up, Russia to conquer or destabilize Ukraine before Europe gets much stronger. That dynamic can spur escalatory moves, such as Russia intensifying its war efforts, mobilizing more troops now, or resorting to riskier military gambits (e.g. covert operations in the Baltics). It’s notable that General Breuer, Germany’s defense chief, recently warned Russia could be capable of attacking a NATO country by end of the decade, given its weapons output ramping up theweek.com. He pointed to the Suwałki Gap (between Poland and Lithuania) as a vulnerable flashpoint theweek.com. Thus both sides are openly gaming scenarios of direct confrontation.

Ukraine Security Commitments & “Reassurance Force”: Alongside arming itself, the EU under Kallas/von der Leyen is pushing for long-term security commitments to Ukraine – essentially tying Europe’s credibility to Ukraine’s fate. Borrell floated a €20 billion Ukraine Assistance Fund for 2024–2027 (the aforementioned UAF) to ensure a steady flow of arms even if war weariness grows theguardian.com. Separately, individual EU nations (France, Poland, etc.) have mulled a “reassurance force” or military training mission stationed in nearby countries to guarantee Ukraine’s security if a ceasefire emerges atlanticcouncil.org. Kallas has been a strong advocate of giving Ukraine a clear path to EU and NATO membership, calling it Europe’s “duty” to integrate Ukraine fully politico.com. She sees this as locking in the gains of resisting Russia – tying Ukraine to the West irreversibly. However, such moves could be a red line for Russia and possibly trigger pre-emptive escalation. Putin has cited NATO expansion as a key grievance; a fast-track NATO accession for Ukraine (even if symbolic while war rages) could provoke extreme Russian reactions (some analysts fear it might even prompt consideration of tactical nuclear use to prevent it). The EU offering interim security guarantees is a more ambiguous step, but still one that could drag the EU into war if fighting reignites after a truce. If, say, an EU “peacekeeping” or observer mission were deployed in Ukraine and came under Russian attack, Kallas would likely urge invoking all available measures in response. The line between EU and NATO gets blurry in such contingencies – another path to unintended wider war.

Rhetorical Framing and the Risk of No Off-Ramps:

Kallas’s and others’ public discourse frames the conflict as a long-term, zero-compromise struggle. She routinely emphasizes that “Russia’s imperialistic dream never died” spiegel.de and that if Putin isn’t decisively defeated in Ukraine, he’ll simply regroup and threaten Estonia or Poland next spiegel.de. In her view, a negotiated frozen conflict or partial settlement would be merely a prelude to the next war. This narrative has been effective in sustaining Western unity through the first 18+ months of the war. It draws on historically justified fears. But it has a double-edged effect: it signals to Moscow that Europe’s goal is Russia’s strategic defeat. Even if Western leaders insist “regime change” in Moscow is not their aim, the rhetoric of war crimes tribunals, reparations (Kallas spearheaded a drive to legally enable confiscation of frozen Russian assets for Ukraine’s rebuilding politico.eu), and total victory can make the conflict existential for Putin’s circle. Their propaganda already claims the West seeks to dismember Russia. Kallas’s stance unwittingly feeds that paranoia. She was the first EU leader put on an official Russian “wanted” list, after her government removed Soviet monuments and a tank memorial in Narva in 2022 sestry.eusestry.eu. The Kremlin absurdly charged her with “desecrating” history. Kallas treated it as a badge of honor – “Proof that I am doing the right thing” she posted, vowing not to be silenced politico.eu. But such episodes underscore how personal the animosity between the current Russian leadership and figures like Kallas has become.

Kallas has also not shied from confronting China in rhetoric. In a Politico live event, she essentially told President-elect Trump to be tough on Russia if he wants to contain China, explicitly linking European and Indo-Pacific security politico.eu. This “two-front” logic – fight the junior partner (Russia) to deter the senior partner (China) – could entangle Europe in Asia’s disputes more directly. Already, von der Leyen and Kallas have aligned the EU’s language on Taiwan closer to the U.S.’s. Just a week ago, after meeting China’s Wang Yi, Kallas publicly reiterated that any attempt by China to aid Russia militarily or undermine sanctions would face severe consequences from the EU (a warning line that EU officials have upheld since 2022). Beijing bristles at Europeans lecturing it or tying Ukraine to Taiwan. If China were to, say, begin supplying Russia with arms (something it has so far avoided in a blatant way), that would escalate the proxy war into a more direct East–West confrontation. Conversely, if a Taiwan crisis erupts, the EU under leaders like Kallas would likely echo U.S. condemnations of Beijing and perhaps provide material support to Taiwan or at least diplomatic support to a U.S.-led response. This is another avenue by which Europe could slide into a “two-front” conflict mindset – effectively treating Russian and Chinese challenges as part of one global contest (the “democracies vs autocracies” frame).

In sum, the combination of heavy armament, maximalist war aims, and confrontational rhetoric pursued by Kallas and allies paves multiple pathways to an expanded war:

Horizontal escalation in Europe: e.g. a Russian stray missile or deliberate strike hits a Polish or Romanian target (perhaps interdicting Western arms), NATO responds, and tit-for-tat military exchanges begin. Europe’s newly militarized posture could then kick into high gear, and within days a regional war could engulf the Baltics or Black Sea region. Kallas’s constant emphasis that “if Russia isn’t stopped in Ukraine, it will strike elsewhere” spiegel.de suggests she’d take any such incident as proof positive and push for robust NATO military action, not restraint.

Vertical escalation in Ukraine: as Europe provides longer-range weapons (e.g. if Ukraine gets missiles that can hit Russia’s heartland or Western fighter jets), Russia might escalate vertically – potentially to using a tactical nuclear weapon in Ukraine or attacking a NATO staging base – to shock the West into backing off. Kallas has explicitly argued against self-deterred limits, but that increases the chance the West crosses a threshold that Russia (in desperation) reacts to with something previously unthinkable. Her likely response to even nuclear coercion would be to demand steadfastness – she has argued Putin must see he cannot frighten us into stopping support.

Transatlantic and Trans-Theater Spillover: If conflict erupts over Taiwan or in the South China Sea, a strongly anti-China EU leadership might support U.S. actions there, prompting China to retaliate economically (cutting Europe off from critical goods) or even by pressuring Europe militarily (e.g. a naval incident in the Mediterranean with China’s growing naval presence). Kallas’s worldview leaves scant room for neutrality in such a scenario – she frames global security as indivisible: “We see Russia, Iran, North Korea, China working together… If the US wants to remain the world’s strongest power, it will have to deal with Russia. The easiest way is to help Ukraine win the war,” she told an audience, effectively binding the European and Asian theaters sestry.eu. Implicitly, that means Europe’s security strategy is linked to U.S. staying engaged worldwide; if the U.S. is in a Pacific war, Europe might feel compelled to take more aggressive stance against Russia (to prevent Russia from exploiting U.S. distraction) or even assist in the Pacific in some form.

Kaja Kallas often references Estonia’s national motto “Never alone” – emphasizing alliances – but Europe under her guidance could find itself more alone if conflicts expand. For instance, her hardline approach could alienate some Global South countries that view Europe as escalating war at the expense of global economic stability (food and fuel crises). Already, key swing states like Brazil, India, South Africa have refused to side with the West’s sanctions on Russia. If Europe doubles down on confrontation, it may lose hearts and minds in much of the world, isolating itself alongside the U.S. and a few Pacific allies. This is a soft-power blind spot of the hawks: focusing so intensely on defeating the adversary that they neglect the broader diplomatic picture.

In conclusion, the policies and posture championed by Kallas and von der Leyen have undoubtedly strengthened Europe’s immediate deterrence and Ukraine’s defense. But they have also set in motion forces – massive arms buildup, maximalist expectations, and more adversarial East–West relations – that, absent careful management, could accelerate Europe down a path to a wider war. The next section will examine some of those fault-lines and blind spots more closely, including economic interdependencies and internal dissent that could either rein in or exacerbate the march toward confrontation.

Fault-lines & Blind Spots: Economic Interdependencies, Dissenting Capitals, and Public Opinion

Despite the façade of unity in Brussels, Europe is far from monolithic in its threat perceptions and willingness to bear costs. The Kallas/von der Leyen agenda faces subtle and not-so-subtle resistance on multiple fronts:

Economic Interdependencies – The China Quandary:

One major blind spot is the EU–China economic linkages. While Kallas talks tough on Beijing, countries like Germany and France remain deeply intertwined with the Chinese market. The EU’s total trade with China was about €700 billion in 2022, and critical European industries (automobiles, luxury goods, machinery) depend on Chinese consumers or components. A confrontational posture towards China – e.g. sanctions over Taiwan or human rights – could invite Chinese retaliation that would hurt Europe’s economy even more than decoupling from Russia did. Europe managed to replace Russian gas in 2022–2023 at high cost, but replacing the Chinese manufacturing base or consumer demand is another matter entirely. For instance, former German Chancellor Olaf Scholz (even as he solidified an anti-Russia stance) has been cautious on China, visiting Beijing in late 2022 with a business delegation and stressing the need to keep dialogue open. President Macron similarly has urged a distinct European approach (“strategic autonomy”) toward China, implying Europe shouldn’t simply follow a hawkish U.S. line. These nuances risk getting flattened by leaders like Kallas, who see the world in more black-and-white terms of democracies vs. autocracies. If Europe were to slide toward a trade war or tech war with China in parallel to the hot war with Russia, the economic blowback could be severe: a Bloomberg Economics analysis estimates a war over Taiwan (which presumably leads to a China-West decoupling) would cost the global economy $10 trillion, dwarfing the shock from the Ukraine war bloomberg.comusip.org. Europe, teetering on recession as of 2025, might face depression-like conditions with energy and supply chains disrupted further. Public support for a hard line would likely crumble in Southern Europe were that to happen. This interdependence is a strategic vulnerability that hawks often downplay. Von der Leyen has coined the term “de-risking” (not full decoupling) with China, aiming to balance security and trade. But finding that balance is tricky when political pressures (e.g. a U.S. push for Europe to sanction China) mount. Kallas will have to navigate the tension between her principled stance and Europe’s economic realities – a blind spot if she misjudges it.

Dissenting Capitals – Hungary, and the Eastern Rift: Not all EU or NATO members share the Baltic/Nordic hawkish posture. The most vocal dissenter is Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, who has obstructed or delayed several EU sanctions packages and aid tranches to Ukraine. While ultimately Hungary has not vetoed core measures (Budapest abstained on the €5 billion EPF increase but let it pass), it continually criticizes the EU strategy. Szijjártó’s comments in March 2024 encapsulate this dissent: “The EU’s strategy in Ukraine is a failure… Europe’s leaders lack the political will to take responsibility for Europe’s losses” europediplomatic.com. He slammed talk of sending EU troops as “alarmingly dangerous” and reminded colleagues that NATO has ruled out direct war with Russia europediplomatic.com. Hungary’s stance is influenced by its own interests (energy dependence on Russia, concern for the Hungarian minority in Ukraine, Orbán’s illiberal ideological alignment with Moscow on some issues). But it resonates with a segment of European opinion that prioritizes a quick peace over a just peace. For example, in Italy, populist voices have questioned whether sanctions hurt Europeans more than Putin, and in Germany, the far-right AfD and far-left Die Linke both propagate narratives critical of prolonging the war. These factions feed off economic grievances and fears of escalation.

In Slovakia, a more Russia-sympathetic government under Robert Fico came to power in late 2023, pledging to halt arms supplies to Ukraine. While Slovakia is a small country, this trend could widen. If more EU states elect leaders skeptical of the war, the EU’s unanimity on tough measures could break. Already the requirement for unanimity on foreign policy is a fault-line. Kallas herself, before becoming High Rep, argued for moving to majority voting on some foreign policy issues – precisely because unanimity gave Budapest (or any outlier) a veto. Indeed, to get around Hungary’s veto threat on an oil embargo in 2022, the EU had to carve out exemptions. If frustration grows, countries might attempt work-arounds (smaller coalitions, using NATO or G7 fora to act without all EU members, etc.). That undermines the image of European unity, which Putin keenly watches for cracks.

Kallas’s forceful style could also alienate potential allies in Western Europe if they feel she’s shaming or lecturing them. The Politico story of her confrontation with Merkel and Macron in 2021 is telling politico.eupolitico.eu. While many now say “Kallas was right” about Putin, the personal dynamics matter. Macron’s snide question to her – “Will you still be PM tomorrow?” politico.eupolitico.eu – hinted at a condescension that hasn’t entirely vanished. Big states don’t like being led by small states. If Kallas oversteps or fails to consult, it could trigger pushback in the Council. We saw a mild version of this when she launched the artillery shell plan without French buy-in; France and others ensured it was scaled down and made a collective initiative. Some diplomats grumble Kallas lacks nuance – “She might need to learn that being right is not enough; you have to bring others along”, as one put it. So a blind spot might be her impatience with consensus-building. In EU foreign policy, you can’t just will a strategy into being; you have to get everyone on board, or at least not actively obstructing.

Western European Public Opinion – War-Fatigue Deepens & Priorities Diversify (July 2025)

Persistent, but softer, support

Germany remains a bell-wether: a February 2025 DeutschlandTrend survey found 67 % still back arming Kyiv, yet only 27 % want to increase aid and an equal share now favours cuts German poll kyivindependent.com eurointegration.com.ua.

EU-wide, an Eurofound e-survey (April 2025) shows support slipping fastest among low-income households and heavy social-media users eurofound.europa.eu.

A December 2024 YouGov tracker confirmed the mood shift: the share backing “support until victory” fell by 15-20 pp across Sweden, Denmark and the UK YouGov trend nationalsecurityjournal.org.

Casualty shock fuels scepticism.

Western estimates now put combined military losses at ≈ 1 million+. A June 2025 CSIS study projects Russian casualties alone to top that mark by summer, with ≈ 250 000 confirmed dead CSIS casualties nypost.com.

UK intelligence collates similar totals of 250 000 killed / 750 000 wounded across both armies en.wikipedia.org. Such figures increasingly drive the question heard in Berlin and Rome: how long should this attrition continue?

Populists surf the fatigue in Germany. AfD polling averages 27–30 % in 2025, wresting second place from the SPD and framing sanctions as self-harm en.wikipedia.org.

Italy. Giuseppe Conte’s Five Star Movement openly votes against new weapons packages, while Matteo Salvini’s League rails at “EU rearmament” divides inside Giorgia Meloni’s coalition jacobin.comiz.rupolitico.eu.

Austria & Slovakia. Vienna saw 20 000 anti-FPO demonstrators in January 2025, many linking defence outlays with rising living costs reuters.com. Parallel rallies in Bratislava criticised PM Fico’s pro-Moscow tilt apnews.com.

Refugees & social-service strain

UNHCR records 6.3 million Ukrainian refugees registered for protection across Europe (Jan 2025), a plateau since mid-2024 reliefweb.int.

An EU Court of Auditors report (Feb 2025) warns cohesion funds “lacked metrics” to gauge school-housing pressure eca.europa.eu consilium.europa.eu.

Energy & inflation back on the agenda

Although euro-area inflation dipped to 2.0 % in June 2025, German households face a 23 % grid-fee-driven gas price jump in January reuters.com cleanenergywire.org. On 8 July 2025 the European Parliament loosened the 90 % gas-storage mandate to contain future price spikes reuters.com. A cold 2025-26 winter, coupled with slower refill rates, could again put energy protests on the streets.

Bottom line (July 2025)

Western publics still reject a Russian victory, but fatigue has morphed from an undercurrent into an electoral force. Absent a decisive Ukrainian breakthrough, which is unlikely, calls for calibrated negotiations—especially from populists—are set to grow louder as economic concerns and refugee integration out-compete foreign-policy idealism in West-European voter priorities.

Kallas and von der Leyen’s circle might underestimate how quickly political winds can shift. In 1914, Europeans marched enthusiastically to war; by 1916, they were disillusioned. Today’s publics are far less casualty-tolerant. While European troops aren’t dying in Ukraine (yet), Europeans see the daily images of slaughter and some ask, “couldn’t we at least try for a ceasefire?” The hawks respond that any ceasefire now would reward Russian aggression and is unsustainable. Strategically they may be right. But if the war drags into 2026 or 2027 with no clear victory, the pressure to prioritize humanitarian concerns (stop the bloodshed) over punitive ones (defeat Russia fully) will mount. Kallas’s hardline stance could then become politically untenable in many democracies. Populists would seize the moment to label leaders as warmongers ignoring their people’s pain.

Another blind spot was, as we have seen, the assumption of unwavering US support. The hawks often say “the US must not waver, we must stay until victory.” But US politics are volatile – as evidenced by Trump’s win in 2024. If Washington really reduces support, Europe faces a watershed. Kallas and von der Leyen’s answer is ReArm Europe – the EU must step into the breach dw.com. But can European publics endure a situation where their leaders ask them to sacrifice even more because the US “abandoned” the cause? Transatlantic coordination is another fault-line: if a rift emerges (like Trump pressing for a quick deal with Putin, which he initially attempted), how will Europe respond? Kallas’s inclination would be to try to persuade or shame Trump into toughness – she literally appealed that he must be “strong” on Russia or risk emboldening China politico.eu. But if that fails, Europe, with Germany at its head, might go it alone in supporting Ukraine, an immense burden. Divisions within Europe could deepen if say, Western European nations lean toward following a US détente with Russia to focus on China, while Easterners refuse.

Humanitarian and Ethical Concerns: Within Europe’s intellectual and religious circles, there are voices warning against a purely militarized approach. The late Pope Francis, for example, had called for peace efforts and not isolating Russia completely. Humanitarian NGOs caution that escalating conflict is causing immense suffering (tens of thousands of civilian casualties, millions of refugees). While European leaders like Kallas emphasize that this suffering is caused by Russia – which is only partially true – the question arises: is the West doing everything it can to minimize human cost, or is it prolonging war by not pushing harder for negotiations at opportune moments? There is no easy answer – and Ukrainians themselves largely reject negotiations that freeze territorial losses. But if down the line Ukrainian public opinion shifts (say if the war stalemates and destruction continues, some Ukrainians might favor a ceasefire), Europe will face a moral and strategic dilemma. Kallas’s stance has been to support Ukraine’s terms no matter what; she says only Ukrainians can decide when/if to negotiate. That is principled. However, one could foresee a scenario where a war-weary Ukrainian government under pressure considers an imperfect peace, and hawks like Kallas might actually discourage it (fearing it undermines broader deterrence of Russia). That could put the EU at odds with the very country it’s backing, an awkward blind spot in policy coherence.

Strategic Blind Spot – No Plan for Russia After Putin (or Post-War Order): Another critique is that hawks lack an articulated vision for a European security architecture after a (hopeful) Ukrainian victory. Historically, major wars end with some diplomatic settlement or new order (Westphalia, Vienna Congress, etc.). Right now, the focus is on winning the war, not on what a stable peace would look like if Russia is defeated or deterred. Kallas and others seldom speak of arms control, confidence-building measures, or future engagement with a different Russian regime. The OSCE, once central to European security, has been sidelined – partly because Russia violated all its principles. But as some analysts note, eventually Europe may need a forum like the OSCE again to rebuild trust and verify agreements europeanleadershipnetwork.org.

Kallas’s generation of leaders is not investing much in those tools; in fact, Russia’s war “dismantled” the previous OSCE-based architecture europeanleadershipnetwork.org, and little has replaced it beyond raw deterrence. The risk is a long-term division of Europe with high chance of flare-ups – a “new Cold War” but potentially more unstable given multiple flashpoints and more actors (China). A truly strategic approach would include thinking about off-ramps: how to get from escalation to de-escalation when the time is right. Right now, that thinking is scarce, at least publicly. Critics like veteran diplomat François Heisbourg have warned that “war aims that are too maximalist can become self-defeating.” If the West signals it seeks Russia’s permanent weakness or Putin’s ouster, it may eliminate incentives for Putin to ever stop fighting. A smarter approach might combine military pressure with offers of a diplomatic pathway (e.g. sanctions relief for withdrawal, security guarantees, etc.). Those offers aren’t on the table currently. It’s unclear if that’s a blind spot or a deliberate choice to not negotiate under duress. But as wars drag on, strategy often has to adapt.

Information Warfare and Public Resilience: One more front is the information war. Thus far, European publics have been kept relatively united partly through effective communication (bordering on indoctrination) about the stakes – e.g., emphasizing Ukrainian bravery, Russian atrocities (like Bucha), and the risk of appeasing a dictator. Kallas excels at this narrative: she often says, “If we fail in Ukraine, we wake up in a more dangerous world” news.err.ee. However, maintaining public resilience might require more than just appeals to history and principle; it might mean tangible proof that policies are working (e.g. Russia is being weakened and Europeans are secure and prosperous). If a protracted war undermines that latter part, no amount of moral exhortation may keep people supportive.

In sum, the fault-lines – economic, political, social – suggest that the path advocated by Kallas and her allies, while morally clear-cut to them, runs through treacherous terrain. Divergent national interests, fragile public consensus, and the potential for major economic pain (especially regarding China) could all crack the façade of unity. The “unelected Euro-elites” thus walk a tightrope: they must achieve enough success fast enough to vindicate their approach before opposition coalesces. If Ukraine were to score a decisive victory soon, the hawks would be vindicated and internal dissent likely quieted. But if the war grinds on into a bloody stalemate or widens, the backlash against those elites could be politically seismic.

Having mapped the intentions and the tensions, we now move to future-casting: Consequences & Scenarios – what might Europe face in the next five years if Kallas’s confrontational agenda prevails, under various escalation trajectories. We outline three possible pathways (limited, regional, systemic conflict) and assess their strategic, economic, and humanitarian costs, drawing on expert projections and historical parallels.

Consequences & Scenarios: Escalation Pathways and Five-Year Cost Projections

European policymakers often speak of not letting the Ukraine war “spiral” into a larger conflagration. Yet the policies in place carry differing probabilities of escalation. Here we sketch three plausible scenarios over the next 5 years (2025–2030), ranging from a limited, contained conflict to a regional war in Europe to a systemic global confrontation, and estimate their costs. Each scenario assumes Kallas’s and von der Leyen’s agenda continues to shape Europe’s stance, and examines how events could unfold and impact Europe.

Scenario 1: Limited War – Protracted Conflict in Ukraine (Status Quo Plus)

Outline: The war in Ukraine grinds on without direct NATO involvement. Neither Russia nor Ukraine achieves a decisive victory; front lines move back and forth in grueling offensives. Europe continues arming Ukraine at a high tempo, and sanctions remain or even tighten, but Russia endures, albeit weakened. No other theaters (e.g. Taiwan) ignite major conflict, keeping it “one-front” albeit with global ripple effects.

Strategic Costs: This scenario essentially extends the present situation for five more years. By 2030, Ukraine would sadly be utterly devastated in parts, and its military and civilian casualties would soar. Strategically, Russia would be severely weakened militarily – its ground forces a spent force, its economy stagnant under sanctions. However, Putin (or a like-minded successor) could remain in power, doubling down on militarism and hostility, waiting for Western unity to crack. The conflict could become a frozen front not unlike the 1916 Western Front, with periodic offensives but no peace treaty.

For Europe, this scenario is a war of attrition that tests its staying power. The European Defence White Paper 2030 authored by Kallas envisioned exactly this possibility – that Russia might rearm for another attempt in ~5 years if given respite atlanticcouncil.org. In a protracted-war scenario, the EU would need to sustain (and likely increase) its support. Already by end of 2023, the EU committed ~€12 billion in economic aid and €5 billion in military aid to Ukraine theguardian.com, with another €50 billion pledged for 2024–27 theguardian.com. Extending that, one might expect the EU to spend €10 billion+ per year on Ukraine aid (military + budgetary) for the next 5 years – around €50–€70 billion total through 2030. Individual countries like Poland, the Baltics, Finland would keep military spending at 3% of GDP or higher (Estonia is already at ~3% plus an extra 0.25% for Ukraine aid politico.eu). Others might grudgingly reach 2.5-5%. Europe’s own rearmament would continue: perhaps not the full €800 billion von der Leyen envisaged (that assumed replacing the U.S. completely), but significant – say EU and UK combined defense budgets rising by €200–€300 billion cumulatively over 5 years compared to pre-war baseline. This is a cost to taxpayers but a boon to arms industries. One side effect is economic trade-offs: money to tanks and shells is money not spent on green transition, infrastructure, or social programs. Europe might see slower growth (or a retraction) as a result (though Keynesian rearmament can boost demand, but it’s not very productive investment).

The global economic impact of a contained war, while serious, is far less than wider war scenarios. A study by Bloomberg Economics estimated that if the war remains contained to Ukraine but drags on, the drag on global output might be around $1.5 trillion in the first year (mostly due to high energy prices and market jitters) theweek.com. Over 5 years, markets and supply chains adjust, so the incremental cost might not multiply linearly. Perhaps the war shaves a few tenths of a percent off global GDP annually – accumulating to maybe $3–5 trillion in lost output over 5 years. High energy and food prices would persist intermittently, especially if Russian supply continues to be disrupted (the 2022 shock saw EU gas prices jump 5–10× briefly, but by 2025 they stabilized at ~2× pre-war levels as alternate supplies came online). Europe might endure permanently higher defense spending (the “end of peace dividend” as one expert put it theguardian.com) and somewhat lower living standards due to decoupling from cheap Russian commodities. But it would be manageable – akin to the burdens of the Cold War, which Europe sustained for decades.

The humanitarian toll in this scenario is grave but geographically limited to Ukraine (and bits of Russia). One could foresee the total number of refugees from Ukraine reaching 10–12 million (up from ~7 million who fled in 2022). Europe would need to integrate many long-term – which it has the capacity to do but at significant social cost (housing, schools, healthcare). Estonian sec-gen Vseviov’s warning “everything is at stake” theguardian.com would still hold; the core principles would remain contested until the war concludes decisively one way or another.

In summary, Scenario 1 is costly – perhaps €50–70 billion direct EU financial cost, >1 million casualties, and a frozen conflict that leaves Russia bitter and revanchist – but it avoids a larger European war or nuclear exchange. It is essentially a worse, bloodier repeat of the Korean War outcome (an unresolved war with an armistice line). Europe could live with it, but it’s a draining status quo that Kallas and others fear simply postpones a bigger showdown.

Scenario 2: Regional War – NATO-Russia Direct Conflict in Europe

Outline: The war in Ukraine spills beyond its borders or triggers Russia-NATO clashes. This could happen via a deliberate (or accidental) Russian attack on a NATO country (e.g. a Baltic state or Poland, perhaps under some pretext or miscalculation) or a NATO decision to intervene directly if Ukraine faces collapse or if Russia uses nuclear weapons in Ukraine. Alternatively, a skirmish escalates – e.g. Russian forces, in trying to interdict Western arms, strike a convoy or base in Poland; NATO responds militarily. War erupts on NATO’s eastern flank, but stays conventional (initially) and theater-limited (not global). China stays out militarily (perhaps urging restraint), and nukes are threatened but not used at first.

Strategic Costs: This scenario is the stuff of NATO war plans. According to many analysts, a full-scale conventional war between NATO and Russia in Europe would likely result in a NATO victory given its combined military might, but not without significant destruction and risk. A RAND war game once predicted NATO could defend the Baltics after initial losses, but the conflict could escalate rapidly. The Week magazine notes that NATO’s military superiority is clear – even excluding the U.S., European NATO has far more troops, tanks, aircraft than Russia theweek.comtheweek.com. As Al Jazeera observed, NATO would “quickly prevail in any conventional war against Russia” due to superior technology and integration theweek.comtheweek.com. However – and it’s a big however – a string of Russian defeats might “force Moscow to use tactical nuclear weapons or face total defeat theweek.comtheweek.com. So the cost scenario must consider that risk.

Assuming nuclear weapons are somehow not immediately used or are constrained (perhaps both sides avoid striking each other’s homeland directly at first), the five-year cost of a regional war would dwarf the contained war scenario. In the first year alone, Bloomberg Economics estimated a Russia-NATO war could drop global output by 1.3% (~$1.5 trillion) theweek.com. Europe’s economy would go into deep recession – trade with Russia (still minor by then) would cease entirely; huge military mobilization would disrupt normal production; investor panic would hit EU markets. There would also be direct destruction: likely heavy fighting in the Baltic region, parts of Poland, maybe Kaliningrad, Belarus, and Ukraine certainly.

Casualties would depend on how quickly NATO could suppress Russian forces (if at all). If NATO established air dominance and overpowered Russian units in weeks, combat deaths might be in the tens of thousands. But if Russia, realizing its disadvantage, fights asymmetrically (scorched earth, mass artillery on cities, etc.), we could see hundreds of thousands of military and civilian casualties across Eastern Europe. The Baltics, with populations of only ~6 million combined, could see significant displacement – perhaps 1–2 million refugees fleeing west to avoid combat. Critical infrastructure in Eastern NATO states could be hit by missiles (as Ukrainian cities were). NATO’s combined forces would likely push into Russia’s immediate border areas (or at least destroy Russian units there), which raises the specter of NATO troops on Russian soil – a scenario Russian doctrine might answer with tactical nukes.

A key cost is the nuclear threshold. If Russia used one or a few tactical nuclear weapons (e.g. on a military formation or supply hub), the calculus changes drastically. NATO might respond with conventional overwhelming force or possibly limited nuclear retaliation. In any case, casualties would spike. Once nukes fly, we risk systemic war (Scenario 3). But even if NATO-Russia war remains non-nuclear, it would be the largest war in Europe since 1945. Modern conventional weapons are devastating; one U.S. bomber sortie can annihilate a battalion. The human cost could easily be in the hundreds of thousands of lives lost in months. Europe hasn’t seen that scale since WWII.

Economic and Social Costs: The immediate global shock of a NATO-Russia war would be higher than Ukraine war: that 1.3% global GDP hit might be conservative if nuclear use is even a possibility (markets could crash beyond that). Europe’s economy could contract several percent. The EU might impose command economy measures – e.g. rationing fuel, nationalizing defense industries for surge production, conscription (yes, mass conscription could return for a full war). Civil liberties would be curtailed under emergency laws. Cumulatively over 5 years, if the war lasts that long (it might not, if it escalates nuclear or ends with Russian collapse), Europe’s lost GDP could be maybe €5 trillion (just a ballpark – roughly 5–10% output loss for a couple years then rebuilding costs). To illustrate, WWII cost the major powers anywhere from 15–30% of GDP annually at its peak in direct war spending – though I suspect a NATO-Russia war would be shorter (either ending or going nuclear within months). If it dragged out in some form for years, Europe would essentially convert into a war economy with perhaps 5–10% of its population under arms and much of industry geared to military needs.

Humanitarian: In addition to casualties, such a war would generate huge refugee flows. Think of Ukraine’s 7 million outflow, then imagine if Poland (pop. 38 million) or Germany (pop. 83 million) had zones of active conflict or nuclear fallout – tens of millions might move internally or to safer countries. The EU’s Temporary Protection Directive, used for Ukrainians, could be triggered for its own citizens – a bizarre twist. The social fabric would be stressed; xenophobic or extremist politics might surge amid chaos; democracy could be at risk in some places (martial law, etc.).

For five-year costing, let’s assume a regional conventional war lasts 6–12 months and is followed by 4 years of tense ceasefire or peacekeeping. The direct war destruction might measure in trillions of euros (Ukraine’s physical damage is >$140 billion so far; a wider war would hit multiple countries’ infrastructure). The EU likely would have to fund a massive post-war reconstruction akin to a new Marshall Plan – perhaps €500 billion or more to rebuild Eastern Europe and possibly parts of Russia.

To quantify roughly: First-year cost: $1.5 trillion global GDP drop theweek.com, >100,000 dead (could be more), maybe 5–10 million new refugees. Five-year total economic cost: maybe ~$3–4 trillion lost output + $1 trillion reconstruction. These are speculative but indicate an order of magnitude far beyond Scenario 1.

In essence, Scenario 2 is catastrophic for Europe, even if it “wins.” It’s exactly the scenario European integration was meant to prevent – a great-power war on European soil. Kallas and von der Leyen’s policies aim to deter this, but by pushing confrontation, some argue they may increase the chance of miscalculation leading here. It’s a razor’s edge: show strength to avoid war, but too much brinkmanship could spark it.

Scenario 3: Systemic War – Global Two-Front Conflagration (WWIII)

Outline: Worst-case: Europe’s confrontations with Russia and China merge into a single systemic conflict. Perhaps NATO and Russia go to war as in Scenario 2, and simultaneously a crisis in East Asia (Taiwan or South China Sea) escalates to U.S.-China war, dragging in allies. Or one war triggers the other (e.g. seeing U.S./NATO busy with Russia, China opportunistically moves on Taiwan, or vice versa Russia strikes NATO if U.S. is tied down in Pacific). The EU finds itself directly involved in hostilities with both Russia and, indirectly or directly, China – a true two-front war pitting the Western alliance vs. a Russia-China (and possibly Iran/North Korea) bloc. Nuclear weapon use becomes highly likely as each side tries to avoid defeat.