Tantura, Anniversary of a buried War Crime

Israels coverup of a Massacre that reverberates till today

Introduction

In May 23, 1948, as the Nakba (“catastrophe”) unfolded across Palestine, a small fishing village named Tantura on the Carmel coast became the site of a brutal massacre. Over the course of one night and day, Israeli militia forces from the Alexandroni Brigade executed scores of unarmed Palestinian villagers after they had surrendered. The victims – mostly young men, including teenagers – were gunned down in cold blood, their bodies dumped into hastily dug mass graves by the sea. For decades, the Tantura massacre remained a fiercely buried secret. Survivors’ testimonies were muted by fear, and Israel’s official narrative cast the events of 1948 in heroic terms, denying any systematic violence against civilians. When an Israeli graduate student named Theodore “Teddy” Katz finally exposed the truth in 2000 through painstaking oral history research, he faced a vicious backlash: lawsuits, public vilification, and the suppression of his work. The Tantura affair became emblematic of how Israeli academia and society silenced inconvenient histories of the Nakba.

At Dor Beach today—a bustling Israeli resort built atop the ruins of Tantura—a Nakba memorial participant lifts an old photograph of the erased Palestinian village. Beneath the sunbathers and swimmers lie the unmarked mass graves of 1948.

This investigative article unearths the story of Tantura – the massacre itself, the eyewitness accounts of Palestinian survivors and even confessions from Israeli soldiers, and the subsequent cover-up that sought to erase this atrocity from history. I will delve into how Katz’s thesis was quashed by legal and institutional forces, situating that episode within a broader pattern of denial in Israel’s historiography. I will also place Tantura in context: far from an isolated incident, it was part of a wider campaign of ethnic cleansing during 1948, as documented by both Palestinian historians and Israel’s own “New Historians” like Ilan Pappé, Benny Morris, and Avi Shlaim, all of whom I have interviewed. Their research – alongside works by scholars such as Nur Masalha, Walid Khalidi, and Saleh Abdel Jawad – reveals that what happened at Tantura was one thread in a tapestry of expulsions and massacres that created the Palestinian refugee problem. I will examine how Israeli propaganda and state institutions have systematically denied or obscured these truths: censoring textbooks to omit the Nakba, deploying Hasbara (propaganda) talking points to cast doubt on atrocities, smearing dissenting historians as traitors or frauds, and suppressing Palestinian memory and oral history. Finally, I address the legacy of this denial today – hearing from descendants of Tantura’s victims who still seek recognition and return, and drawing connections to Israel’s continued displacement of Palestinians in the occupied territories. To underline my point I have interviewed two actual survivors of the Tantura massacre, one elderly lady in Jordan and a Gentleman in Germany. Both interviews are available on my Youtube channel.

Seventy-seven years after 1948, the ghosts of Tantura still haunt the present. Confronting this buried truth is not only an act of historical justice, but a necessary step in dismantling the colonial myths that perpetuate violence to this day. What follows is a journey into a deliberately forgotten massacre – and the urgent moral imperative to remember.

The Massacre at Tantura: Night of May 22–23, 1948

In the darkness of midnight on May 22–23, 1948, the Palestinian coastal village of al-Tantura fell to Zionist forces. Located about 35 kilometers south of Haifa with around 1,500 residents, Tantura had thus far survived the war’s onslaught. But one week after Israel’s declaration of statehood, the 33rd Battalion of the Alexandroni Brigade (a unit of the Haganah, soon-to-be Israel Defense Forces) launched an attack to capture the village. Following a brief battle – in which around 20 villagers were reportedly killed fighting and the rest surrendered – the victors turned suddenly, and savagely, on the vanquished.

As dawn broke on May 23, the occupied village witnessed scenes of terror. Israeli soldiers began executing unarmed Palestinian captives en masse. Dr. Adnan Yahya, the male survivor I interviewed in Germany, described scenes we usually associate with NAZI Germany, scenes so gruesome that I will not repeat them here. His cousin Fayzeh Yahya complemented this narrative when I visited her in Jordan, but from a woman’s perspective, because the Israeli’s did different things to men and women.

Tantura 1948, this is how the “Land without People” looked like before it was destroyed.

According to testimonies from both Palestinian survivors and Alexandroni veterans, the killing happened in two distinct phases:

Phase 1: The Rampage. Immediately after Tantura’s remaining villagers had raised white flags, a shot rang out – either a stray sniper or panicked confusion – and in response, the Alexandroni troops went on a murderous rampage. Witnesses recall that enraged soldiers started spraying bullets into crowds of detainees. One Israeli eyewitness later said a particularly beloved Jewish fighter had been hit by sniper fire after the surrender, enraging his comrades into a bloody frenzy. In this first eruption of violence, at least 70–100 Palestinian villagers were killed on the spot. “They lined people up and shot them dead in the streets,” remembered survivors. Haganah men went house to house, and the surrendering villagers “had no mercy visited upon them,” as one account put it.

Phase 2: Systematic Executions. Once the initial rampage subsided, a more deliberate slaughter followed. Israeli intelligence officers and local paramilitary members (including settlers from nearby Jewish colonies like Zichron Ya’akov and Binyamina) organized the remaining Palestinian men and women into separate groups and systematically executed the men one by one. Using lists of names, they sought out any men suspected of having fought or of possibly hiding weapons. In reality, many victims were ordinary unarmed villagers with no role in combat. Eyewitnesses – including some horrified Jewish soldiers – later testified that groups of seven to ten bound prisoners at a time were led either to the village cemetery or to a wall by the mosque and shot in the back of the head. This “cleansing” operation continued until roughly another 100 men had been executed. It only ceased when a few Alexandroni officers from Zichron Ya’akov protested that too many innocent people were being killed as ‘enemy’, belatedly halting the bloodbath. Dr. Adnan Yahya also told me about a particular gruesome revenge rape in full sight of the victims family.

By the end of May 23, the toll was staggering. Adding the roughly two dozen killed in combat, some 200–250 Palestinians from Tantura had been slain after the village’s surrender. One Jewish Alexandroni soldier tasked with burying the dead later recalled counting 230 bodies in total. Virtually all males aged 13–30 who had stayed in the village were executed. Only a handful of young men survived, either by hiding under corpses or through last-minute intervention by sympathetic Jewish neighbors. “They left no one alive,” admitted Alexandroni veteran Joel Solnik, who described Tantura as “one of the most shameful” episodes he witnessed in the 1948 war.

Palestinian survivors’ testimonies paint a harrowing picture of those hours. Some women and children witnessed husbands, fathers or brothers taken away at gunpoint, never to return. Mustafa Masri, who was a young boy in 1948, later recounted watching soldiers execute his entire family before his eyes. Decades later, speaking to researcher Teddy Katz, Masri’s voice still trembled with trauma: “Believe me, one should not mention these things… I don’t want them to take revenge on us. You will cause us trouble,” he pleaded, terrified that even telling the truth could invite retribution. The weight of fear and grief kept many survivors silent.

Researcher Teddy Katz listening to his tapes with testimonies.

Those who were not killed outright were dealt a cruel fate. In the aftermath of the massacre, the Haganah rounded up all remaining villagers – women, children, and the elderly – and marched them to the nearby beach. Families were torn apart: men of “fighting age” were separated out and shipped to detention camps for 18 months, while the rest of the community was loaded onto trucks and expelled from the area. Most ended up in the adjacent village of Fureidis, which, along with Jisr al-Zarqa, was one of the only Palestinian villages between Haifa and Tel Aviv spared destruction (ironically because their labor was needed by neighboring Jewish settlements). Even that was temporary – ultimately, the men of Tantura who survived imprisonment were driven into exile, sent to the West Bank (then under Jordanian control) to join their uprooted families. A few Tantura families managed to remain inside the new State of Israel, but only thanks to the personal intervention of Jewish acquaintances who vouched for them. This should remind us even while we witness the atrocities that Israel currently unleashes on Gaza and the West Bank, that not all Jews, or better Israelis, are vengeful murderers.

Meanwhile, Tantura as a village ceased to exist. Once its residents had been killed or expelled, Zionist forces looted what they could and quickly moved to wipe the village off the map. An Israeli document from June 1948 notes: “We have tended to the mass grave, and everything is in order.” Indeed, the executioners had worked to cover their crime: survivors later recalled being forced at gunpoint to dig trenches to bury the dead. At least one large mass grave was dug by Palestinian prisoners in the village cemetery and filled with bodies, while another grave near the beach was filled with those executed there. Dr. Adnan Yahya described to me, on camera, how he and his friend, facing machine guns, had to throw his friends wounded father into the mass grave, - while he still was alive.

By mid-June, reports reached Israeli army headquarters complaining about “unburied corpses in the village” causing stench and disease, prompting the army to dispatch burial crews to finish interring the victims properly. In subsequent months, the remnants of Tantura’s homes were systematically demolished or incorporated into a new Israeli kibbutz (named Nahsholim) established on its lands. Even the grave sites were concealed: part of the main mass grave was later paved over as a parking lot for the Dor Beach resort, where unsuspecting beachgoers sunbathe above the remains of an entire community.

One house has survived to this day though. Incidentally this house belonged to Dr. Adnan’s family and it is hard for me to describe my own feelings when I showed Dr. Adnan a clip where his niece, Hala Gabriel, was able to visit it. If you have subscribed to my YouTube channel you (hopefully) will get notified when I release this story.

Hala Gabriel sitting at the ruins of her family’s home, the only surviving building of Tantura.

What happened in Tantura was ethnic cleansing in microcosm. An Israeli officer candidly confirmed to Katz that in 1948, each local commander had “full authority to do with the inhabitants as he saw fit, whether they surrendered or were taken prisoner.” The usual Haganah tactic was to encircle villages on three sides, leave one “escape corridor” open, and terrorize the inhabitants into fleeing (a method used in many villages to avoid dealing with large captive populations). At Tantura, however, poor coordination led to a complete encirclement by land and sea, trapping the residents inside. With no escape route, 1,500 Palestinians fell into the hands of the occupiers, leading to the massacre and mass expulsion that followed. Ilan Pappé – one of Israel’s dissident historians – notes that the massacre was the direct outcome of these circumstances: “The concentration of so large a village in the hands of the occupier… produced the rampage, the massacre, and the executions,” he wrote. Some Alexandroni fighters justified the carnage as a “security” measure – eliminating potential resistance – while others simply took revenge or settled personal scores. Either way, the result was the same: an entire village was wiped out. Tantura joined the grim roster of Palestinian localities subjected to massacre in 1948 – one of dozens of such atrocities that would only come to light years later.

Silencing History: The Teddy Katz Affair and Israeli Academia’s Backlash

For over fifty years after 1948, the massacre of Tantura remained a carefully guarded secret. Official Israeli histories described the fall of Tantura as a normal military victory, perhaps noting that the village’s Arab inhabitants “fled” or were taken prisoner, but saying nothing of mass executions. Palestinian survivors, now refugees scattered in camps, certainly remembered – the story of the bloodbath was passed down in whispers within families – but their accounts had no platform in Israeli society or academia, which largely denied that deliberate atrocities accompanied the state’s birth. This wall of silence was finally breached in the late 1990s, thanks to an unlikely individual: Theodore “Teddy” Katz, an Israeli graduate student (and self-described Zionist) at Haifa University.

Katz, then in his 50s, embarked on a master’s thesis researching the 1948 depopulation of villages in the Haifa region. Fluent in Arabic, he decided to use oral history – tape-recorded interviews with witnesses – to reconstruct what happened in villages like Umm Zinat and Tantura. Over several years Katz conducted more than 60 hours of interviews, speaking with both Palestinian survivors (in Israel and the West Bank/Gaza, as well as some in exile) and Jewish veterans of the Alexandroni Brigade. This was groundbreaking; few if any Israeli scholars had bothered to seek out Palestinian oral testimonies of 1948 until then. Katz’s research yielded explosive findings: in one chapter of his thesis, he documented in chilling detail the massacre at Tantura, estimating that about 200 unarmed villagers were killed after surrendering. Notably, Katz had obtained corroborating testimonies from Alexandroni soldiers themselves who took part – otherwise, he later noted, his work would likely have been ignored outright. One veteran told him bluntly, “There were shameful things there… we didn’t leave anyone alive.” Another admitted to counting over 200 bodies. Katz even unearthed a handful of declassified IDF documents hinting at the crime: a report of “irregularities” by troops in Tantura, and a brigade communiqué about taking care of a “mass grave” to prevent epidemics. Piece by piece, the thesis built a damning case that Tantura had witnessed a war crime.

In March 1998, Katz submitted his thesis, entitled “The Exodus of the Arabs from Villages at the Foot of Southern Mount Carmel in 1948”, to the University of Haifa. It passed with flying colors, receiving the highest grade in the department. For a brief moment, it seemed this long-suppressed story might enter the historical record through scholarly channels. But in January 2000, word of Katz’s findings reached the Israeli media – and the backlash was swift and ferocious. The Hebrew daily Ma’ariv ran a headline article on the Tantura massacre, bringing Katz’s revelations to the general public. Almost immediately, outraged veterans of the Alexandroni Brigade (many of whom still viewed themselves as heroes of Israel’s independence war) closed ranks in denial. They launched a defamation campaign against Katz, vehemently insisting that no massacre had ever occurred and that he was smearing their reputation. Within days, the Alexandroni Veterans Association filed a libel lawsuit against Katz, demanding over 1 million shekels in damages.

What followed was a stark illustration of Israeli academia’s role in preserving national myths. Rather than defending its student, Haifa University effectively threw Katz to the wolves. University officials, especially senior faculty in the Department of Eretz Israel Studies (a department often aligned with nationalist narratives), immediately cast doubt on Katz’s competence and integrity. They insinuated that his research was flawed or even fabricated, and withdrew institutional support. Katz, who had been slated to receive a special award for his excellent thesis, found his name literally whited-out with correction fluid (“Tippex”) from the program. His status at the university became equivalent to that of a suspended student, and any hopes he had of an academic career were dashed in an instant. The message was clear: by uncovering a massacre that contradicted the heroic Zionist narrative, Katz had committed an act of treachery in the eyes of the academy’s gatekeepers.

Despite this hostile climate, Katz prepared to defend his work in court. With the help of Adalah, a Palestinian-run legal center in Israel (one of the few willing to assist him), he gathered a team of pro bono lawyers. The libel trial opened in December 2000. In the courtroom drama that ensued, truth took a backseat to procedural attacks. The prosecution combed through Katz’s 200-page thesis and seized on minor inconsistencies – a handful of citation errors and slight mistranslations out of hundreds of references. For example, in one instance Katz’s Hebrew summary of a witness’s words used “Germans” instead of “Nazis”; in another, he inferred a killing from a survivor’s account that wasn’t explicitly stated (though the implication was clear). These were quibbles, not substantive refutations of the overall massacre narrative. In fact, no less than 224 out of 230 specific references in the thesis were found to be accurate and undisputed. None of the former soldiers who spoke to Katz dared take the stand to deny their recorded testimonies. Nonetheless, Israeli media and academia honed in on the few discrepancies to discredit Katz.

After two days of trial, Katz’s lawyers were optimistic: the prosecution had exhausted its attacks on footnotes, and the heart of the matter – the eyewitness evidence of mass killings – was about to be examined. Katz and his supporters believed that if those tapes and transcripts were aired in court, the truth of Tantura would finally get a public hearing. But that moment never came. Under tremendous pressure and in ill health (Katz had suffered a stroke weeks earlier), Katz was ultimately convinced – some say coerced – into signing a retraction “apology” to settle the case out of court. In a late-night meeting on December 21, 2000, without two of his attorneys present, Katz heeded the advice of a third lawyer (who was also a relative) and the urgings of the university’s legal adviser that giving in was in his best interest. Family and friends, worried for his health and finances, also urged him to end the ordeal. Katz signed a statement that can only be described as Orwellian: he repudiated his own research and declared that, “after checking and re-checking the evidence, it is clear to me now, beyond any doubt, that there is no basis whatsoever for the allegation that the Alexandroni Brigade… committed killings of people in Tantura after the village surrendered.” He went on to “disassociate” himself from any conclusion that a massacre had occurred. In effect, he was forced to deny the very truth he had uncovered – a forced confession reminiscent of show trials.

The ink was barely dry on this coerced apology before Katz regretted it. Within 12 hours, he attempted to retract the statement and reinstate his defense. But the damage was done. The judge refused to reopen the case, focusing only on the technical question of Katz’s right to reverse his settlement (and ruling he could not). Thus, the libel suit ended without any judicial examination of whether a massacre had actually taken place. Israeli news outlets trumpeted Katz’s capitulation as proof that the massacre was a lie. Major newspapers labeled him a “fabricator” and “pseudohistorian”, suggesting he invented a massacre for political reasons. Right-wing commentators rejoiced that an “anti-Israeli narrative” had been debunked. In a particularly cruel twist, even some left-leaning Israeli intellectuals piled on – the prominent journalist Tom Segev allowed that “maybe there was a massacre, but it met the wrong historian,” implying Katz wasn’t up to the task. The Israeli public was largely left with the impression that Tantura was a false rumour. If no massacre happened, then – by extension – perhaps none of the Palestinian claims of 1948 ethnic cleansing were true. The episode thus served to reinforce the comforting national myth that any accusations of Israeli atrocities are Arab fabrications or mistakes.

Within Haifa University, the witch-hunt continued. The libel settlement did not satisfy the guardians of the official history. The Israeli State Archivist and others pressured the university to strip Katz of his Master’s degreeentirely. The university convened investigative committees to pore over Katz’s tapes and his supervisor’s conduct, looking for excuses to annul the thesis. In the end, Katz was allowed to keep his degree (after making some minor corrections), but his reputation was irreparably tarnished. He vanished from academic circles, effectively blacklisted. The chilling effect on others was unmistakable: no young Israeli scholar was likely to touch the subject of 1948 massacres again for years.

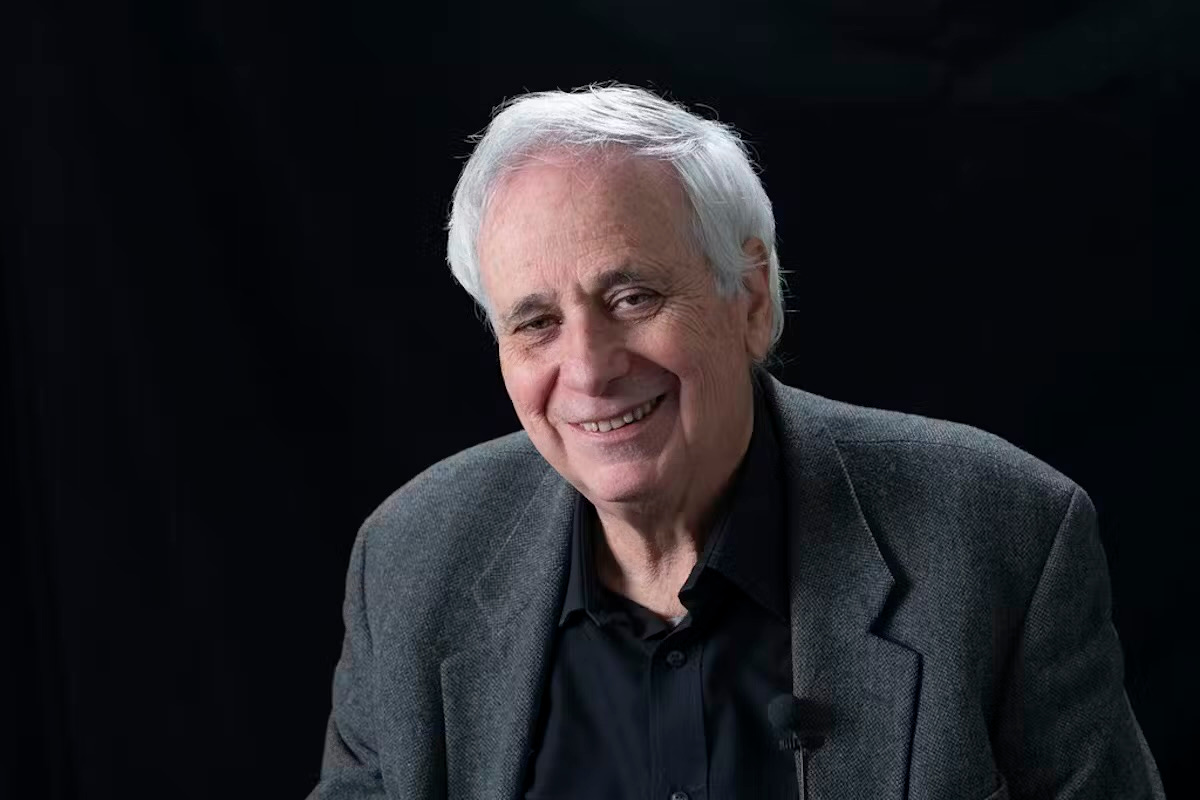

One of the few Israeli academics who stood by Katz was Dr. Ilan Pappé, then a senior lecturer at Haifa University. Pappé had been promoting what he called “post-Zionist” history, urging Israelis to confront the dark aspects of 1948. During the Katz affair, Pappé went so far as to post some of Katz’s interview transcripts on the university’s internal website for colleagues to read. Those transcripts, he reported, contained “horrific descriptions of execution, of the killing of fathers in front of children, of rape and torture” from both Arab and Jewish witnesses. “After reading the transcripts,” Pappé wrote, “a number of people, even if they had reservations about the quality of Katz’s research, no longer had any doubts about what happened in Tantura” Nevertheless, Pappé’s efforts to rally academic support fell largely on deaf ears. He found himself increasingly isolated and vilified by peers. Within a few years, Pappé too would be driven out: in 2007, amid death threats and official censure for his vocal criticism of Israel’s Nakba denial, he resigned and left Israel to teach in the UK. (As Al Jazeera noted, Pappé “faced a harsh response from Israeli society” and was fired from his tenured position at Haifa University after continuing to insist that 1948 was a case of ethnic cleansing). In my interview with him Pappé described why, despite having won a court case against the University, he felt compelled to leave Israel.

Ilan Pappé: we are witnessing the end of the Zionist project.

The silencing of the Tantura massacre was thus achieved through a combination of legal intimidation, academic complicity, and media spin. It demonstrated how far Israel’s establishment was willing to go to suppress a truthful narrative that threatened national mythology. Yet ironically, attempts to bury the truth only delayed its resurrection. Katz’s original recordings survived, and decades later they would resurface in the public domain (notably in a 2022 documentary film) to corroborate what he had found. The old soldiers’ code of silence also began to crack with time – some veterans, approaching the ends of their lives, finally confessed to what they did in 1948. As we will see, these confirmations have emerged, vindicating Katz’s work and refuting the lies that were told about him. But before examining the present-day reckoning, we must understand how Tantura fits into the bigger picture of 1948. What happened in this village was not an anomaly; it was part of a clear pattern of expulsions and massacres that accompanied the founding of the Israeli state – a pattern long denied, but thoroughly documented by historians and researchers over the years.

Ethnic Cleansing by Design: Tantura in the Context of the Nakba

The massacre and depopulation of Tantura cannot be dismissed as a rogue incident or heat-of-battle frenzy. It was one node in a wider policy of “ethnic cleansing” implemented during the 1948 war, as Zionist forces conquered territory for the new state of Israel. Israeli “New Historian” Benny Morris – who spent years researching declassified Israeli archives – bluntly concluded that “without the uprooting of the Palestinians, a Jewish state would not have arisen.” In other words, the mass expulsion of Palestinians was not an accidental byproduct of war; it was a precondition for Israel’s creation. The link to my interview with him is in the Sources list below.

From late 1947 through 1948, some 750,000 Palestinians (three-quarters of the Arab population of what became Israel) were systematically removed or fled under duress, and over 400 towns and villages were emptied of their inhabitants. Plan Dalet (Plan D) – a master plan issued by the Haganah in March 1948 – set the stage. As described by historian Walid Khalidi, Plan Dalet was literally a “master plan for the conquest of Palestine.” It authorized Israeli commanders to destroy villages and expel residents in order to secure the territory allotted to the Jewish state (and beyond). The plan’s guidelines explicitly called for encircling villages, searching and disarming them, and in case of resistance “the population must be expelled outside the borders”. In the months that followed, these instructions were put into practice on a massive scale. By the end of 1948, over 500 Palestinian localities had been depopulated; many were razed to the ground, others were repopulated with Jewish immigrants and renamed. The Palestinian people’s very existence on their land was being erased – the process Palestinians know as Al-Nakba.

Fleeing Palestinian villagers in 1948

Tantura’s fate was a direct result of this policy framework. Its strategic location on the coast made it a target early in the war. As part of the Haganah’s coastal “clearing” operations south of Haifa, Alexandroni Brigade units had already depopulated villages like Kafr Lam and al-Sarafand in preceding weeks. Alexandroni’s standard modus operandi was to expel inhabitants during the attack – giving people a route to flee instead of capturing them. But if a population could not or did not flee (as in Tantura), harsher measures ensued. The brigade commander’s “full authority” to “do as he saw fit” with surrendered Arabs resulted, in Tantura and elsewhere, in summary executions and massacres aimed at instilling terror. Historian Ilan Pappé, in his seminal book “The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine”, documents how multiple massacres punctuated the campaign of expulsions in 1948 – from Deir Yassin in April (where over 100 were slaughtered by Irgun/Lehi militias) to Lydda in July (where over 200 were massacred by Israeli troops, including soldiers under the command of Yitzhak Rabin), to al-Dawayima in October (where an Israeli unit killed upwards of 100 villagers).

How many such atrocities occurred? Even conservative estimates by Israeli historians acknowledge at least two dozen massacres during the 1948 war. Benny Morris himself (initially skeptical of some Palestinian accounts) recorded “roughly 800 [Palestinian] civilians and prisoners of war” killed by Israeli forces in at least 24 separate incidents that can be defined as massacres. More comprehensive research by Palestinian scholar Saleh Abdel Jawad and others points to dozens more smaller massacres or one-off executions that accompanied the expulsions. An analysis of United Nations and IDF archives cited by BADIL (a Palestinian refugee rights center) identified more than 30 documented massacres in 1948, with 24 in the northern region (Galilee and Haifa area), 5 in the center, and 5 in the south. One Israeli military historian, Aryeh Yitzhaki (formerly of the IDF archives), went further to suggest that “more than 100” massacres were committed by Israeli forces, including about 10 large-scale ones. Among the **“most well-known” he listed Deir Yassin, al-Dawayima, and Tantura. In short, Tantura was not an aberration – it was part of a pattern. It ranks among the notorious massacres of the Nakba, albeit one that remained less internationally known, perhaps because its perpetrators succeeded in covering it up for so long.

It’s important to emphasize that what happened in 1948 was not a series of unfortunate accidents by rogue troops, but rather the realization of long-standing ideological goals. Nur Masalha has chronicled the pre-war Zionist thinking about “Transfer” – a euphemism for the removal of Arabs. Zionist leaders from the 1930s onward, including future Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, had discussed and prepared for the forcible transfer of the Arab population out of the Jewish state-to-be. By 1948, those ideas translated into action under the fog of war. Ben-Gurion’s government and military command openly decided not to allow the return of Palestinian refugees, even those who had fled violence, in order to permanently alter the demographic balance. When the war ended, the new State of Israel quickly passed laws to confiscate the lands and properties of the 750,000 expelled Palestinians, ensuring they could not come home. The magnitude of what took place is why Pappé and others use the term “ethnic cleansing”: it was a deliberate purge of an ethnically defined population from their native territory.

To understand the climate in which the Tantura massacre was buried, one must also recognize the powerful Israeli national narrative forged in the war’s aftermath. The official story in Israeli discourse for decades was that in 1948, the new Jewish state fought a defensive war against overwhelming Arab aggression; that Palestinians fled of their own accord or at the behest of Arab leaders, and that Israeli forces upheld a high moral standard (“purity of arms”) throughout – meaning any deviations were isolated and regrettable, not policy. For many years, Israeli archives were classified and the public accepted this narrative largely unchallenged. Palestinian accounts of expulsions and massacres were dismissed as propaganda or fantasy. In 1988, for example, the eminent Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi published All That Remains, a monumental documentation of the 418 villages destroyed in 1948. It included Tantura’s depopulation, though at the time Khalidi did not have evidence of the massacre and thus only noted the village’s occupation and the expulsion of its people. Such works, along with collected oral histories by Palestinians, were largely ignored by Israeli academia. Only in the late 1980s and 1990s, as some Israeli archives opened, did a new generation of Israeli historians start corroborating what Palestinians had been saying all along. Benny Morris’ 1988 book “The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–49” broke some ground by acknowledging that hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were expelled and that Israeli forces were often implicated in atrocities – though Morris stopped short of using the term “ethnic cleansing” and at times seemed to rationalize the events as a forced necessity of war. Avi Shlaim, in “The Iron Wall” (2000), similarly shattered many myths by detailing how Israel’s leadership from Ben-Gurion onward took a hardline stance of territorial maximalism and refusal to repatriate refugees, preferring an “iron wall” of military force to secure the new state. I had the rare opportunity to speak with Avi twice: first as a historian, and later as a victim of the Israeli-orchestrated bombing campaign against Iraqi Jews—a covert operation designed to terrify them into abandoning their homeland and immigrating to Israel (see Sources below).

But Ilan Pappé, Katz’s ally, emerged as the most outspoken voice, explicitly arguing that 1948 constituted an organized ethnic cleansing operation – a crime for which, he contends, Israel must bear moral responsibility.

Each of these scholars faced pushback, but together their works (often drawing on Israeli government archives) confirmed a narrative that Palestinians had lived as truth: that the Nakba was not a voluntary exodus but a violent dispossession. It’s telling that only when Israeli Jewish historians began publishing these findings did parts of Israeli society begin to grudgingly concede aspects of the Nakba. As The Guardian noted, by the 2000s “a new generation of revisionist Israeli historians rejected the old official narrative that the Palestinians… were responsible for their own misfortune.” Even an Israeli prime minister, Ehud Olmert, gingerly acknowledged Palestinian “suffering” in 2007. But a full reckoning was far off. Indeed, others doubled down on denial – for instance, Likud leaders like Benjamin Netanyahu insisted that teaching the Nakba narrative was akin to spreading enemy propaganda.

Tantura, therefore, sits at the crossroads of history and memory. On one hand, the event itself in 1948 was a quintessential example of the Nakba’s violent expulsions – the sort of episode systematically documented by historians like Pappé, Khalidi, Masalha, and even in parts by Morris. On the other hand, the post-war suppression of what happened at Tantura exemplifies the decades-long Israeli effort to uphold a sanitized national story. When Katz tried to bridge those two realms – injecting the suppressed truth of Tantura into the public record – the weight of Israel’s denial apparatus came crashing down on him.

Yet facts have a way of resurfacing. Today, thanks to continued research and brave testimony, we know that Tantura was “ethnically cleansed” in 1948 as part of Israel’s foundation – and that this was not an isolated aberration, but policy. The villagers of Tantura were not the only ones. From Galilee to the Negev, Palestinian civilians were killed in dozens of locales and hundreds of thousands were uprooted from their ancestral homes. This realization is profoundly challenging to the heroic self-image Israel cultivated. It requires an acceptance that Israel’s creation involved not just valour and sacrifice (which for Jewish Israelis it certainly did), but also mass violence against an indigenous population and the erasure of their presence. Recognizing this doesn’t undermine the fact of Israel’s existence today, but it strips away the moral absolution often claimed for its founding. And that is why acknowledging Tantura – and the Nakba at large – remains such a taboo in the Israeli establishment, to the point that extraordinary lengths of denial have been deployed.

Propaganda, Denial and the Battle for Memory

From the outset, the Israeli state and its supporters have been heavily invested in denying or reframing the narrative of 1948. Admitting to massacres like Tantura not only tarnishes the legacy of Israel’s “War of Independence” but also potentially bolsters the Palestinian demand for justice and return. Thus, a variety of propaganda techniques and censorship tools have been used to obscure these events. The Tantura massacre was denied through a combination of silence, deflection, and character assassination – tactics emblematic of the broader approach to the Nakba in Israeli discourse.

One major arena of denial has been the education system. For decades, Israeli school curricula simply omitted any Palestinian perspective on 1948. The term “Nakba” – Arabic for catastrophe, referring to Palestinians’ dispossession – was long unmentioned in textbooks. In 2009, in a telling move by the right-wing Netanyahu government, Israel’s Education Ministry went so far as to ban the word “Nakba” from Arab school textbooks that serve Israel’s Palestinian citizens. This ban, announced by education minister Gideon Sa’ar, was explicitly aimed at preventing acknowledgement of 1948 as a catastrophe for Palestinians. “There is no reason to present the creation of the Israeli state as a catastrophe in an official teaching program,” Sa’ar stated, adding that the education system shouldn’t “promote the delegitimization of our state.” The very inclusion of the Palestinian experience was framed as a treasonous act. Such textbook censorship ensures that generations of young Israelis grow up learning only one side of the story – the Zionist triumph – with little to no awareness that their country’s birth entailed the destruction of hundreds of villages and the expulsion of an entire people. Even references to Palestinian suffering that had briefly made it into some materials under earlier, more liberal administrations were excised by nationalist officials. This systematic shaping of historical memory means the average Israeli is often genuinely unaware of events like the Tantura massacre, or considers them baseless “Arab tales.”

Beyond formal education, the Israeli government has long engaged in Hasbara (propaganda) campaigns internationally to solidify its version of history. A core Hasbara talking point regarding 1948 has been: “No massacres – Palestinians left voluntarily or under orders from Arab armies.” This narrative was repeated in Israeli diplomacy and echoed by sympathetic journalists and academics worldwide for decades. It’s a narrative that has been thoroughly debunked by historical research (no credible evidence ever emerged of a general order by Arab leaders telling Palestinians to leave; on the contrary, most fled due to direct Jewish military attacks or fear thereof). Yet it remains a persistent trope among Nakba-deniers. We even see it crop up in contemporary discourse – for instance, some opponents of the Tantura documentary in 2022 claimed, “If there really was a massacre, why didn’t the villagers report it widely at the time? They just left like everyone else.” Such arguments ignore the reality that survivors did speak (to anyone who would listen), and news of atrocities like Deir Yassin certainly did spread and sow panic among Palestinians. But Israeli propagandists rely on the broader public’s ignorance to cast doubt on each specific atrocity.

When direct denial wasn’t enough, the strategy has also included character assassination and defamation of those who challenge the official narrative. We saw how Teddy Katz was labeled a fraud and nearly erased from academia for daring to document Tantura. Similarly, Ilan Pappé was relentlessly attacked in Israel – ostracized by colleagues, threatened by politicians, and ultimately forced out of his job – after he vocally supported Katz and accused Israel of ethnic cleansing. The Al Jazeera report on the Tantura film noted that Pappé “was ridiculed and fired from his tenured position at Haifa University” because of his stance on 1948. Other Israeli scholars and journalists who have given voice to Palestinian history often find themselves tarred as “self-hating Jews” or “traitors.” The goal is to discredit the messenger so as to invalidate the message. Even Benny Morris, who is far from a leftist (he ultimately remained a Zionist who justified the expulsions), was lambasted by some when he first published his findings; later, when he hardened his stance and suggested Ben-Gurion should have expelled all Arabs, right-wing circles rehabilitated him as a sort of begrudging truth-teller. The consistent pattern is that only a narrative that absolves Israel of intent to do wrong is acceptable. Those who say otherwise are to be marginalized.

Suppression of Palestinian voices is another key aspect. Palestinian historians and institutions have meticulously recorded their peoples’ Nakba memories for decades – in memoirs, oral history projects, and scholarly works. But Israeli institutions have generally dismissed these sources as biased. “There are decades of meticulous scholarship by Palestinians that could have told you all of this,” observed one Palestinian commentator, “but the only reason to believe the Israeli narrative over the Palestinian one is pure racism.” Indeed, as long as a Palestinian said it, official Israel assumed it must be a lie – a mindset rooted in colonial attitudes that natives are unreliable narrators of their own suffering. This began to shift slightly only when Israelis themselves – via archived documents or soldier testimonies – “confirmed” what Palestinians had been saying. A Tweet highlighted by Al Jazeera put it succinctly: “Colonial perpetrators, colonial academics, and colonial archives are automatically endowed with the authority to ‘narrate’.… At this point, believing the Israeli narrative of the Nakba over the Palestinian one is an act of pure racism.” In the case of Tantura, Palestinian survivors like Dr. Adnan and Fayzeh Yahya had recounted the massacre decades earlier, and Palestinian media like Palestine Remembered preserved testimonies of victims’ families. But such accounts were ignored in Israel – until Katz produced taped interviews of Alexandroni vets essentially admitting to the killings. That double standard continues to this day in much of the discourse.

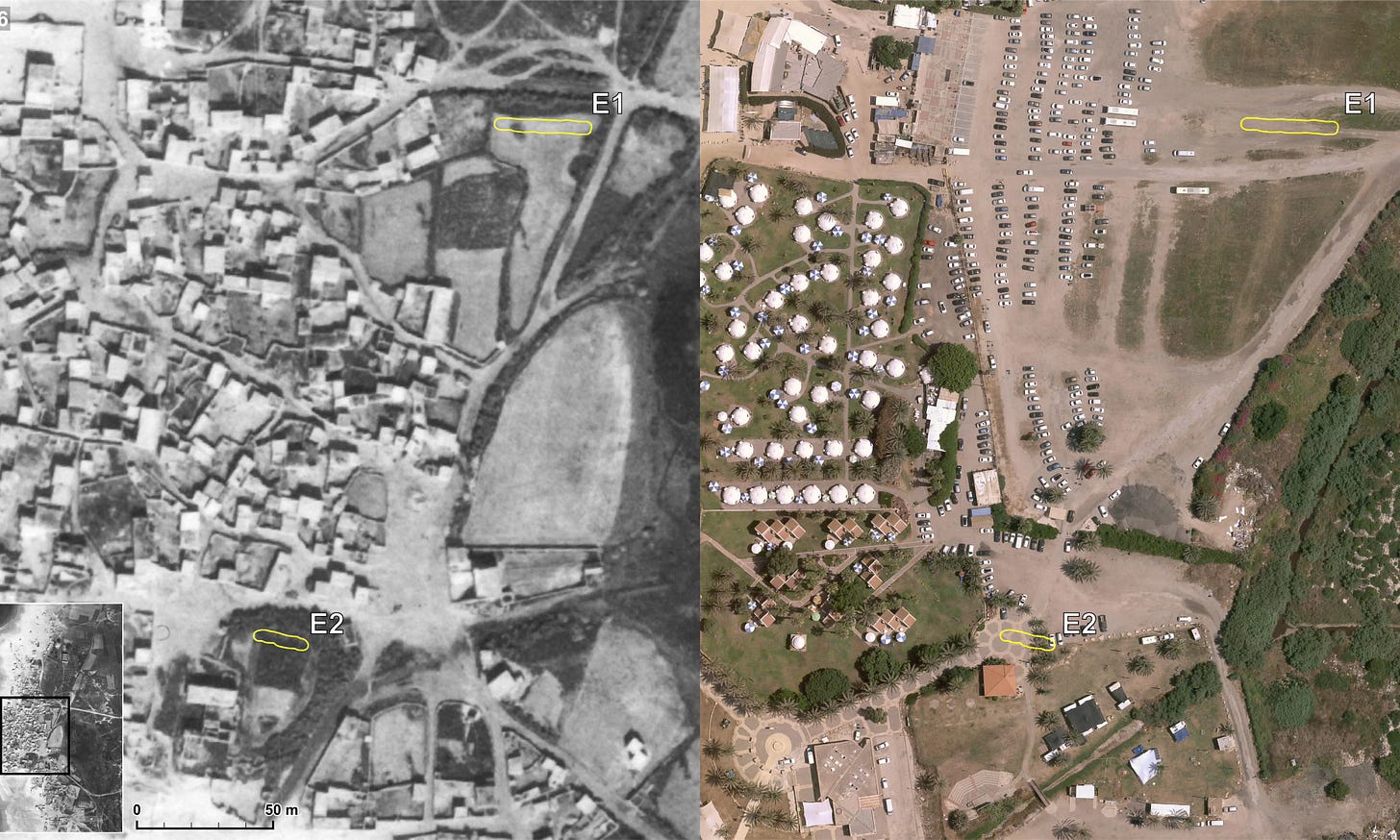

The Israeli state has also employed more concrete methods of memory suppression. Physical remnants of Palestinian existence have been removed or obscured – villages bulldozed, Arabic place-names replaced with Hebrew ones, mass grave sites hidden under leisure facilities, parking lots or closed military zones. For instance, the mass graves at Tantura were unmarked and inaccessible; it took until 2023 for advanced forensic and cartographic analysis (by Forensic Architecture and others) to pinpoint their likely boundaries under the Dor Beach parking lot and a kibbutz area. Even now, there is resistance to formally memorializing these graves. Meanwhile, Israel’s state archives have been selectively closed off when inconvenient. In recent years, evidence emerged that an Israeli Defense Ministry department (MALMAB) systematically re-classified many 1948 documents that had previously been accessible – including reports on expulsions and killings – explicitly to prevent them from fueling “negative” narratives. This revelation, reported by Israeli journalists, confirmed that the government actively curates the historical record to maintain denial.

Then there are the legal and political measures to quash Palestinian remembrance. In 2011, the Israeli Knesset passed what’s commonly called the “Nakba Law,” which authorizes the government to cut funding from any public institution (like schools or municipalities) that commemorate the Nakba as a day of mourning. The law’s intent is clear: to make it financially punitive for Palestinian citizens of Israel (who make up about 20% of the population) to publicly mark May 15th as a day of grief. It doesn’t outright criminalize saying “Nakba”, but it creates a chilling effect. As a result, many Palestinian schools and community centers inside Israel avoid official Nakba ceremonies, or do so behind closed doors. The very act of remembering is made suspect. Similarly, permits for Nakba-related events are often denied, and memorial monuments are not allowed (contrast this with the extensive Israeli state commemoration of Jewish history, including traumatic events – the double standard is glaring). Even references to the Nakba in arts or media can trigger backlash; for example, when an Israeli NGO, Zochrot, which is dedicated to raising awareness about destroyed Palestinian villages, staged exhibits or installed memorial plaques at depopulated village sites, they faced hostility and sometimes vandalism of their signs. Zochrot’s work on Tantura – bringing Israeli visitors to tour the site and see the remaining mosque ruins – has been invaluable in educating some Israelis, but it remains a niche effort, often demonized by the right wing.

Hasbara abroad has similarly sought to police the narrative. Israeli diplomats and advocacy groups vigorously protest when Nakba or 1948 expulsions are mentioned in international forums. They pressure publishers and filmmakers to include the “Israeli perspective” (which often means downplaying or “contextualizing” the harsh facts). A classic example is how Israeli officials respond to news of potential war crimes investigations: rather than engage with the claims, they label them as “anti-Semitic” or part of a plot to delegitimize Israel. The idea that Israel committed mass atrocities in its founding is seen as an assault on its legitimacy; thus any messenger of that idea is attacked accordingly. In the case of the 2022 documentary film “Tantura” by Israeli filmmaker Alon Schwarz, there was a concerted effort by some pundits in Israel to discredit the film. They argued it was rehashing a “lie” and claimed (falsely) that no new evidence was presented. Notably, Haaretz – Israel’s leading liberal newspaper – actually supported the film and ran a headline stating that veterans had “finally come clean” about the mass killing at Tantura. But other outlets and commentators, especially on the right, blasted it. The film’s release reignited debates, showing that the propaganda of denial still clashes with emerging truths. Younger Israelis who saw the film expressed shock – “we never learned about this in school!” – a testament to how effective the suppression has been. Schwarz, the director, said he was driven to make the film after discovering Katz’s tapes and being appalled at how Katz was treated. The film let audiences hear former Alexandroni soldiers in their own voices admitting to shooting unarmed men and dumping bodies. It’s hard to call an old sabra IDF veteran a liar when he calmly says on camera that yes, we killed them. And yet, denialists still tried: one ex-soldier sued to prevent the film’s footage of his admission from being used (unsuccessfully). A small fringe even accused Schwarz of “editing tricks” or the soldiers of false memory. This shows the almost pathological denial that some cling to – no amount of evidence is ever enough, because acknowledging it is too shattering to the national myth.

In Israeli collective memory, 1948 has been enshrined as a heroic saga – “the few against the many,” a miracle of survival and triumph. That narrative has room for noble sacrifices and perhaps a few regrettable excesses, but not for premeditated massacres of civilians. To protect this cherished self-image, the state and society have treated Palestinian memory as a threat. The suppression of the Tantura story for so long was a case in point. However, with each passing year, more archival evidence surfaces and more witnesses speak out (before it’s too late – these 90-something-year-old vets are among the last living participants of 1948). As that happens, the propaganda of denial becomes harder to sustain. Modern technology, too, plays a role: forensic studies like the one conducted in Tantura can literally uncover the ground to reveal grave sites. It is fitting that in May 2023, on the 75th anniversary of the Nakba, researchers announced they had identified multiple possible mass grave locations in Tantura – knowledge that activists are now leveraging to demand official recognition and memorialization.

Forensic Architecture analyzed aerial photos from the British mandate era and identified possible mass graves.

Nonetheless, the struggle over historical narrative continues. Hasbara efforts now often take a new line: instead of blanket denial (which is increasingly untenable), they shift to justification and relativization. For example, some Israeli commentators concede that “bad things” might have happened like Tantura, but then quickly add: “It was war, atrocities happen in all wars; look at what others did; the Jews were fighting for survival,” etc. This is a move from denial to trivialization. Benny Morris exemplifies this shift. By 2004, he acknowledged dozens of Israeli-perpetrated massacres and rapes in 1948, yet infamously told an interviewer: “There are circumstances in history that justify ethnic cleansing” and that he thought Ben-Gurion didn’t expel enough Arabs. Such shocking candor – essentially endorsing the Nakba – ironically aligns with the truth of what happened, but tries to normalize it as something necessary or even laudable. In the face of undeniable evidence, some have chosen to say “So what? We had to do it.” This, too, is a propaganda line, aimed at absolving moral guilt. It shows how the goalposts move: first claim it didn’t happen; when proved it did, argue it was justified.

Meanwhile, the Palestinian narrative has persisted in the face of all attempts to erase it. Families pass down keys to homes in Tantura and other villages, even as those homes are long gone. Refugee camp murals depict the lost locales. Organizations like Zochrot within Israel, or archives maintained by institutes like the Institute for Palestine Studies, keep memory alive. And increasingly, some Israeli Jews – especially younger ones and those exposed to alternative education – are starting to listen. But they do so often in opposition to their state’s official stance.

Legacy of Denial and the Ongoing Nakba

Seventy-seven years after the Nakba, the legacy of denial around events like Tantura continues to exact a toll – not only on historical truth, but on the prospects for reconciliation and peace. For the descendants of Tantura’s survivors and victims, the wounds of 1948 remain open. Many ended up in refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza, Lebanon, or Syria, where some still reside today, barred from returning to their ancestral seaside village. Others rebuilt lives elsewhere in Palestine/Israel; for instance, a number of Tantura families integrated into Fureidis (the nearby village where many were initially sent). Yet, whether in exile or a few kilometers away, these families have lived with the knowledge that the land beneath Dor Beach is a mass grave containing their fathers and grandfathers. And until recently, they have lived with the frustrating knowledge that the wider world knew little and cared less about this crime.

Take the story of Dr. Adnan’s niece, Hala Gabriel, a Palestinian-American woman and film maker, whose family was from Tantura. Hala grew up hearing fragments of how her uncle narrowly escaped death during the massacre. In my interview with him you will hear how he was lined up to be shot after throwing countless corpses in a freshly dug mass grave, - and how he got away.

Determined to uncover her family’s history, Hala traveled to Israel/Palestine and sought out the truth of Tantura. In interviews, she described standing on the beach where her relatives were killed, and even meeting face-to-face with an Alexandroni veteran who took part. “Benzion (Benjamin) Pridan (Friedman) the commander who led the attack, told me if he had caused harm to my family then he apologizes,” Hala recounted incredulously, “as if there was any doubt!” That half-hearted apology – “if” I harmed you – exemplified the evasiveness typical of those who spent a lifetime refusing to fully own up. For Hala, and many like her, such encounters stir deep anger and trauma. Yet they also illustrate the importance of having these stories told. Through her upcoming documentary, Hala Gabriel aims to ensure that her generation and future ones do not forget. She notes that Palestinians in Israel live in constant fear of speaking openly, a legacy of being a minority under a state that has criminalized their narrative. Overcoming that fear – by documenting oral histories and sharing them globally – is a form of resistance to erasure. An interview with Hala is in the making, so subscribe either here on Substack or on YouTube if you don’t want to miss it.

On the Israeli side, there are even descendants of the perpetrators grappling with this legacy. In a remarkable personal testimony published by Zochrot in 2024, an Israeli woman named Yael revealed that her own father was among the Alexandroni veterans who led the campaign to silence Katz and deny the Tantura massacre. As a teenager, she watched her father organize the libel lawsuit and insist no massacre happened. Deep down, she doubted him and felt ashamed, but she stayed silent out of filial duty. Years later, after her father’s death, Yael watched the Tantura documentary and was shaken to realize he had lied – that he likely knew very well about the slaughter, even if he claimed not to have been personally present that night. “The film made it clear to me that my father, who presented himself as a righteous man, had lied,” she wrote. “We will never know whether he took an active part… He claimed not to have been there. But in an interview with Teddy [Katz], parts of which feature in the film, he admits to knowing what happened.” Yael describes the emotional toll of this realization and how it even drove her to leave Israel for a time, unable to bear living in a state that refused to acknowledge its crimes. Her courageous reflection shows that the truth, once known, can deeply unsettle even those raised on the national myths. It also underlines an anti-colonial insight: the colonizer society, by denying the humanity of the colonized and refusing to face its wrongs, ends up poisoning itself with lies. Healing, for both colonized and colonizer, begins with truth-telling.

Crucially, the denial of past ethnic cleansing is directly connected to present-day policies. Palestinians often speak of the “ongoing Nakba” – the idea that the process of displacement begun in 1948 has never really stopped. Israel today continues to uproot Palestinians, albeit on a smaller scale, through mechanisms like home demolitions, land confiscation, and de facto expulsion of communities. In the occupied West Bank (under military control since 1967), entire villages like Khan al-Ahmar or the communities in Masafer Yatta face forcible eviction to make way for Jewish settlers or military zones – an eerie echo of 1948. In East Jerusalem, Palestinian families in Sheikh Jarrah are fighting eviction orders as settler organizations seek to take over their homes, using Israeli laws that allow Jews to “reclaim” pre-1948 properties while barring Palestinians from doing the same. Each of these acts is enabled by a narrative that negates Palestinian rights and history. If Israeli society were widely conscious and remorseful about Tantura and the Nakba, could it so blithely watch new displacements unfolding? Likely not. Thus, denial of past crimes makes repetition of similar crimes easier. It creates a moral numbness. Indeed, some Israeli officials explicitly draw inspiration from 1948. Not long ago, in 2021, a prominent Israeli politician, now a minister, Bezalel Smotrich, declared in the Knesset to Arab lawmakers: “It’s a mistake that Ben-Gurion didn’t finish the job in 1948 and throw you all out.” This chilling statement – effectively wishing for a more complete ethnic cleansing – shows how the far-right in Israel venerates the Nakba as something to replicate, not apologize for. Smotrich later doubled down, saying of a Palestinian town in 2023, “Huwara needs to be wiped out; the State of Israel should do it.” When such genocidal language comes from high officials with little consequence, it underscores that the denial has metastasized into outright pride for some. They don’t deny Tantura because they think it’s a lie; they deny it because deep down they think it was justified and should perhaps be done again, and admitting it would complicate doing it again. It’s a frightening feedback loop: mythologize the past to enable injustice in the present.

Yet, there is some room for hope as well. The persistent work of historians, human rights groups, and even documentary filmmakers has started to crack the wall of denial. The Israeli public today is more aware of the term “Nakba” than it was 20 years ago (even if many still reject its implications). Educational initiatives by NGOs are providing alternative narratives to those willing to listen. Internationally, the Nakba is increasingly recognized; in 2023 the United Nations for the first time officially commemorated Nakba Day, to Israel’s diplomatic chagrin. And importantly, Palestinian survivors and their descendants continue to assert their right to memory and justice. The Tantura families, for example, have recently been organizing – forming a committee to demand Israel acknowledge the massacre and protect the mass grave sites. With Adalah’s legal help, they filed a petition in 2023 to mark and preserve those graves at Dor Beach. One can imagine a future where a memorial stands by that beach, informing visitors of what lies beneath. Such truth-telling monuments exist in many other societies reckoning with dark pasts (for example, markers at massacre sites in Bosnia or memorials to indigenous peoples in North America). Will Israel one day allow a plaque at Tantura? At the moment it seems far-fetched – the government would fiercely oppose it. But civil society pressure, combined with international scrutiny, could slowly make it possible. Already, coverage in mainstream outlets like Haaretz and The Guardian about Tantura’s mass graves has put Israeli authorities on the spot.

For Palestinians, the primary “justice” sought is the right of return – the ability for refugees and their descendants to go back to their original homes or lands. In the case of Tantura, that would mean allowing those families to live in the area again, or at least in Israel as citizens. This is anathema to most Israeli Jews, who fear it would undermine the Jewish demographic majority. But without acknowledging the right of return (even symbolically, even if actual implementation is negotiated), there is no closure. The people of Tantura were expelled unjustly; their descendants remain displaced by that injustice. Denying the crime goes hand in hand with denying their right to remedy. Conversely, recognizing the crime is the first step towards any meaningful reconciliation or solution. Perhaps one day a compromise could be reached – say, a limited return or compensation – but not as long as Israel’s official line is “no crime was committed, we owe nothing.”

This is why the fight over memory and narrative is so crucial. It’s not just about history books; it’s about the present and future. As long as a nation defines its identity by the erasure of another, true peace will elude it. Decolonization of the mind – the willingness to confront one’s own side’s sins – is necessary for decolonization on the ground.

For Israelis, adopting an anti-colonial perspective means rejecting the complacent view that might makes right, and that the state’s founding violence was automatically justified by Jewish suffering. It means understanding that two truths can co-exist: yes, Jews fought for survival in 1948 and yes, in the process they ethnically cleansed Palestinians. Recognizing that does not equate the Nakba with the Holocaust (a common strawman argument used to silence discussion – of course they are different phenomena). It simply places the Nakba in the category of historical injustice that must be addressed, not denied. Many nations have dark chapters; facing them is a sign of maturity, not weakness.

For Palestinians, having their truth acknowledged is validation of their humanity. When a massacre like Tantura is finally recognized by the perpetrators’ society, it is a restoration of dignity to the victims and survivors. It is also a measure of relief – that they were not crazy or liars for remembering what they lived through. The burden of proof they’ve carried for decades can be set down.

As the Nakba enters global awareness more, and as Israeli society faces mounting moral questions (including prominent human rights groups now labeling Israel’s rule over Palestinians as “apartheid”), the façade of pristine virtue in 1948 becomes harder to maintain. Memory activists are chipping away at the national amnesia. Each guided tour of a destroyed village, each article in Israeli media about a massacre, each testimonial video circulating online, contributes to a slow shift.

Conclusion: Confronting Buried Truths, Dismantling National Myths

The saga of Tantura – from the massacre in 1948, to the half-century of silence, to the brave exposure and fierce suppression around 2000, and finally to the gradual vindication of the truth in recent years – encapsulates the broader challenge at the heart of Israel/Palestine. It asks whether a nation built on denial can ever fully heal or be at peace with its neighbors or itself. The historical and moral imperative facing Israel is to confront these buried truths and to dismantle the national myths that have thus far prevented honest self-reflection.

For Israelis of conscience, acknowledging the Tantura massacre and the Nakba is not about wallowing in guilt or assigning collective blame to today’s generation for past events. It is about taking responsibility for the present. It is about saying: Yes, this happened. It was wrong. We should acknowledge it, teach it, memorialize it – and crucially, learn from it so that it never happens again. Such acknowledgment could open the door to reconciliation gestures, like formally apologizing to refugee communities, preserving massacre sites as historical landmarks, and including Nakba education in Israeli schools (just as Germany teaches about the Holocaust as part of ensuring “never again”). It can also influence policy – for example, making Israel more cautious about using force to displace people today, and more open to at least partial realization of the Palestinian right of return (even symbolic family reunifications or visits to village sites would be a start).

On the Palestinian side, having Israelis confront these truths would be hugely meaningful. It would validate their enduring fight for recognition and rights. It is not a substitute for actual rights, but it creates a climate where discussing remedies becomes possible. The experience of other conflicts shows that reconciliation is only realistic when the perpetrator side admits what it did. Imagine if an Israeli prime minister stood at Dor Beach and acknowledged the massacre of Tantura’s men – how powerful a gesture of humanity that would be, and how it could ease the path for Palestinians to, perhaps, consider forgiving (though never forgetting) and moving toward a shared future. We are far from that point, but it’s a vision to hold.

Crucially, confronting the past is also an imperative for truth itself. Beyond the political calculus, there is a basic moral duty to honor the memories of those killed unjustly. The young men of Tantura who were lined up and shot one by one – their story deserves to be told honestly, their suffering deserves to be acknowledged. Keeping them invisible all these years added a second indignity atop their murder. As the Israeli scholar Yehuda Elkana (a Holocaust survivor) once argued, “true reconciliation begins when the victimizer acknowledges the suffering of the victim as part of the victimizer’s own history.” In this case, Israelis must accept the suffering of Palestinians in 1948 as part of Israeli history, not something external or denied.

The dismantling of myths is never easy. Myths are comforting; they provide a tidy narrative of heroism or innocence. But when myths are built on the erasure of an entire people’s trauma, they become dangerous lies that perpetuate injustice. The myth that “no massacre happened at Tantura” sustained itself for decades, but ultimately collapsed under the weight of evidence. So too may other myths – such as “the Palestinians left willingly” or “the Arab-Israeli conflict started because Arabs irrationally hated Jews.” Replacing these with factual, nuanced history does not negate Israel’s right to exist or Jews’ right to security – rather, it contextualizes the very real Palestinian claim to justice.

In many ways, Israel is now at a crossroads similar to other settler societies that have had to face their original sins (like America with its indigenous genocide and slavery, or Australia and Canada with their treatment of First Nations). Some choose the path of contrition and repair; others resist and double down on denial. The latter path only entrenches bitterness and conflict. The former offers a possibility – however slim – of a future not built on domination but on shared humanity.

The story of Tantura, once suppressed, now resurfaces to demand attention. It asks: will we listen to the ghosts in the sand? The survivors are aging, the eyewitnesses are almost gone. Yet their recorded voices and their descendants’ voices ring out powerful, - as I can confirm from personal experience.

Breaking the silence is a form of justice. As one Palestinian tweet cited in outrage after the latest revelations put it: “At this point the only reason to believe the Israeli narrative of the Nakba over the Palestinian one is pure racism… There are decades of scholarship by Palestinians that could have told you all of this.” It’s time – far past time – for that scholarship, those voices, to be given their due.

Unburying the truth of the Tantura massacre is a step toward unburying the larger truth of the Nakba. And unburying the Nakba is essential to understanding the roots of the conflict and finding a just solution. The ground at Tantura literally holds the bones of history. To walk on that beach without knowing what lies beneath is to walk in willful ignorance. The task of this generation, Israelis and Palestinians alike – and all who stand in solidarity with universal human rights – is to ensure that ignorance is banished by understanding.

In recognizing what happened in May 1948 in that village by the sea, we affirm a simple principle: no people’s suffering should be erased, no matter who caused it or what rationales they invoke. For the sake of the dead of Tantura, for the sake of the living who still endure an unresolved legacy, and for the sake of future generations who deserve an honest foundation on which to build peace – the truth must be told and the myths must be dismantled. Only then can Israelis and Palestinians begin to imagine a new narrative: not of conqueror and conquered, not of colonizer and displaced, but of two peoples acknowledging a painful past and working together to ensure it is never repeated. The road to that future begins by facing the ghosts of Tantura and saying, we see you, we remember, and we will not let your truth be denied any longer.

Further Links:

My interview with Fayzeh Al Yahya, a survivor of the Tantura massacre.

My interview with Benny Morris: Benny Morris, the ugly faces of Israel

My interview with Avi Shlaim: Israels Creation Myths

Depending on when you read this you will find here the links to the interviews with Dr. Adnan and Fayzeh Yahya, Hala Gabariel and Ilan Pappe’ (publication pending).

Sources:

Ilan Pappé – “The Tantura Case in Israel: The Katz Research and Trial,” Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Spring 2001), pp. 19-39.

ore.exeter.ac.uk Pappé examines Teddy Katz’s research on Tantura and the ensuing libel trial, providing detailed accounts of the massacre (approx. 200 villagers shot after surrender) and the academic backlash.

Ilan Pappé – The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (2006). Pappé’s book situates Tantura within the broader 1948 ethnic cleansing, describing how Plan Dalet gave commanders carte blanche to expel or kill, and that Tantura’s full encirclement led directly to the massacre.

Benny Morris – The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949 (1988) and 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (2008). Morris documents the causes of the 1948 exodus and records Israeli-perpetrated massacres. He notes roughly 24 massacre incidents, with about 800 Palestinian civilians/POWs killed by Israeli forces.

Avi Shlaim – The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World (2000). Shlaim provides context on Israel’s post-1948 policies, showing the leadership’s refusal to allow refugee return and its reliance on military force (the “iron wall”). This context helps explain why atrocities like Tantura were systematically denied.

Nur Masalha – Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of Transfer in Zionist Political Thought, 1882-1948(1992). Masalha’s research shows that the idea of “transfer” (expulsion) of Arabs was discussed by Zionist leaders well before 1948, demonstrating that depopulating villages like Tantura was not a spur-of-the-moment decision but aligned with ideological goals.

Walid Khalidi – “Plan Dalet: Master Plan for the Conquest of Palestine,” Middle East Forum (1961) / Journal of Palestine Studies reprint (Autumn 1988). Khalidi calls Plan D a “master plan for the conquest of Palestine” and details its instructions to destroy villages and expel populations, directly relevant to what happened in Tantura.

Walid Khalidi – All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated in 1948 (1992). Khalidi’s encyclopedic work documents Tantura’s occupation and depopulation. (It inadvertently omitted mention of the massacre since evidence emerged later). Provides demographic and geographic data on Tantura pre-1948.

Saleh Abdel Jawad – “Zionist Massacres: the Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem in the 1948 War,” in Massacres in the Palestinian Memory (Arabic, 2007). Abdel Jawad lists at least 68 villages where Israeli forces committed killings or massacres in 1948. His research offers a comprehensive view of widespread violence, including Tantura.

BADIL Resource Center – Al-Majdal Magazine, Issue No.7 (Autumn 2000), article “Massacres and the Nakba.” Summarizes research that over 30 massacres occurred in 1948. Cites an Israeli source suggesting more than 100 locales saw atrocities, with Tantura named among the major ones.

Haaretz (Adam Raz) – “There’s a Mass Palestinian Grave at a Popular Israeli Beach, Veterans Admit – and No One Cares,” Haaretz, 20 Jan 2022. Reports on new testimonies from Alexandroni veterans in the “Tantura” film confirming the mass killing and identifying the Dor Beach parking lot as covering at least one mass grave of ~200 victims.

The Guardian (Bethan McKernan) – “UK study of 1948 Israeli massacre of Palestinian village reveals mass grave sites,” The Guardian, 25 May 2023. theguardian.com Covers Forensic Architecture’s investigation using aerial imagery and testimonies, which identified two probable mass grave sites in Tantura and spurred a legal petition by Adalah to protect them.

The Guardian (Ian Black) – “1948: No catastrophe, says Israel, as term Nakba banned from Arab textbooks,” The Guardian, 23 Jul 2009. theguardian.com Discusses Israel’s Education Ministry removing “Nakba” from school books for Arab citizens, an example of institutional censorship of Palestinian history. Quotes officials like Gideon Sa’ar and Netanyahu equating Nakba references with anti-Israeli propaganda.

Al Jazeera – “Palestinians call for probe into Israeli massacres in Tantura,” Al Jazeera English, 22 Jan 2022. aljazeera.com Covers reactions to the Tantura documentary and Haaretz report. Includes the Palestinian Authority’s call for international accountability, notes how Israeli archives and historians (Morris, Pappé) handled the topic, and that Pappé was forced out in 2008 for calling 1948 a case of ethnic cleansing.

Mondoweiss (Jonathan Ofir) – “Nakba denial in Israel is long and deep, new documentary shows,” 21 Jan 2022. Reviews Alon Schwarz’s Tantura documentary and Israel’s denial history. States “more than 200 Palestinians were gunned down by a Zionist militia” at Tantura and provides dimensions of a mass grave (35 x 4 m) containing the victims. Also recounts Katz’s ordeal and the veterans’ libel suit mondoweiss.net.

Mondoweiss – “On the Road to Tantura: Interview with Hala Gabriel,” 27 Aug 2015. mondoweiss.net An interview with filmmaker Hala Gabriel, a refugee’s daughter from Tantura. She describes meeting the Alexandroni commander (Benzion Pridan) who attacked Tantura and his half-apology, highlighting the unresolved trauma for descendants and the denial by perpetrators.

Zochrot – Testimony: “On the Massacre in Tantura” by Yael, 3 Mar 2024. zochrot.org Personal account by the daughter of an Alexandroni veteran involved in silencing the Tantura story. She expresses shame and describes the intergenerational impact of denial, and how the 2022 Tantura film revealed her father’s lies.

Forensic Architecture & Adalah – “Executions and Mass Graves in Tantura, 23 May 1948” (Report, 2023). Used aerial photos, survivor testimony (e.g., Adnan Yahya) and 3D models to confirm one known mass grave by the beach and discovered a second in a former orchard near the mosque. Confirms graves were dug for those executed after surrender forensic-architecture.org. Collaborative project supporting a legal effort to mark these sites.

BADIL – “Ongoing Nakba” and recent displacement context. From IMEU’s Plan Dalet explainer: notes that Israel has continued policies of expulsion after 1948, inside 1948 borders and in 1967 occupied territories, fueling what Palestinians call the “ongoing Nakba.” Provides modern examples and even quotes (e.g., Smotrich 2021 statement about expelling Palestinians) imeu.org.

Haaretz (Opinion, Yoav Gelber) – “The Tantura Myth: It Makes No Sense That Palestinian Villagers Never Mentioned a Massacre,” Haaretz, 7 Oct 2022. (Referenced via secondary sources). Gelber originally doubted Tantura but by 2022 acknowledged that Palestinian witnesses had in fact spoken of it, refuting his own earlier skepticism (showing a shift among some Israeli historians as evidence mounted).

Reuters – “Israel bans ‘catastrophe’ term from Arab schools,” 22 Jul 2009. Mirrors the Guardian report on banning “Nakba” in textbooks, illustrating official suppression at the policy level.

The word “hasbara” is generally taken to mean Israel’s “public diplomacy”, although “information warfare strategy” more reflects reality, but Israel also has an “internal hasbara” which aims to keep its citizens ignorant of the truth about the Jewish state’s history - its a shame the film Tantura didn’t go into this.

https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article-abstract/128/1/371/7098144

Horrific.